War lost, peace won: ceremonial handover of the flag on the Maytény plain…

On April 30, 1711, after the Peace of Szatmár had been signed by Károlyi Sándor and the Kuruc leadership, the Kuruc army of about 12,000 men laid down their arms on the Maytény plain, ending the struggle for freedom led by Ferenc Rákóczi II since 1703. With this, in the absence of Prince Rákóczi Ferenc II, the Hungarian War of Independence led by him came to an end.

The Hungarian hopes of a balanced struggle in the first phase were overshadowed from 1707 by the Anglo-Austrian superiority in the War of the Spanish Succession, which enabled the Habsburgs to turn more and more forces against Rákóczi. It became clear that Rákóczi and his Kuruc army would not be able to achieve victory against the Imperials on their own, so the prince used every means at his disposal to encourage his French, Dutch, and Swedish allies to support him. The Act of the Diet of Ónod in 1707 dethroned the Habsburgs (13 June 1707).

Rákóczi’s main goal was to formalize the French-Hungarian alliance, to make Hungary’s struggle for independence part of the general European war, and to have the fate of the country that had declared its independence decided at an international conference. However, the support sent by King Louis XIV (r. 1643-1715) steadily diminished, while Rákóczi unsuccessfully tried to find a candidate for the throne of Hungary.

The Bavarian elector Emmanuel Maximilian declined the invitation in opposition to King Joseph I (r. 1705-1711), and Rákóczi’s second choice, Frederick William of Prussia, also refused to enter into conflict with the Habsburgs. Nevertheless, Rákóczi assumed that he would take the Hungarian throne, and planned a war outside Hungary in 1708, trying to persuade Frederick William to accept the Hungarian crown by victories in Moravia and Silesia.

The Kuruc armies set off for the Moravian border, but suffered a disastrous defeat in the Battle of Trencsén on 3 August 1708. The battle of Trencsén began with high hopes because Siegbert Heister, who was leading the Imperial army, was deceived several times during the march, and the battle began with the Austrian general’s troops retreating before the Prince’s troops, who appeared to be much stronger than the reports had suggested. However, Rákóczi’s general staff was too long inactive, and only Pekry Lőrinc’s infantrymen finally moved against Heister, but they too advanced timidly. The fate of the developing battle was decided by an unfortunate accident when the prince’s horse broke its neck in an unfortunate jump.

Rákóczi was rescued from the enemy attack by Bercsényi László, but many of the Kuruc thought that the prince had lost his life; their momentum was broken, so Pálffy Miklós and Heister easily overcame them and inflicted thousands of casualties on the rebels. After the defeat at Trencsén, Rákóczi’s remaining hopes of victory were lost, and after the defeat, several leaders defected to the Labanc side (most famously Ocskay László), and Bottyán János, one of the prince’s most successful generals, died in 1709. The fighting subsided, and the prince tried to win over Tsar Peter the Great (r. 1682-1725) to support the Hungarian uprising, without success.

In 1710, the Kuruc army, reinforced by French and Swedish troops, was defeated in the last major battle of the War of Independence, near Romhány, and the main actors in the war were no longer armies but famines and the plague in an exhausted Hungary. Rákóczi’s army gradually retreated to the area delimited by the castles of Kassa, Munkács, Ungvár, and Tokaj, the former starting point of the uprising. To stall for time, the prince allowed General Károlyi Sándor to contact Count Pálffy, and in January 1711, negotiations began in Vaja, which could not be successful due to Rákóczi’s unrealistic demands.

You can read more about the life of Károlyi Sándor on my page:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/general-karolyi-sandor-1669-1743/

However, unlike the prince, Károlyi wanted real peace, so in March he secretly swore allegiance to King Joseph I, and without Rákóczi’s knowledge, he began peace negotiations with Pálffy. In the meantime, the prince called a Diet in Huszt for his dwindling people, and on 6 April he left for Poland to again seek the help of Peter the Great, who was fighting along the Prut in the Northern War, Károlyi called another Diet in Szatmár to publicise the secret deal he had made with Pálffy, which had many supporters in the Kuruc army.

Here is the life of Pálffy János, too:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/famous-people/palatine-palffy-janos-1664-1751/

Rákóczi sent a futile proclamation from Poland inciting to war, but it had no effect. On 29 April, Károlyi agreed with the Labanc (pro-Habsburg) general on the most important points of the armistice. On 30 April 1711, the 12,000-strong Kuruc army laid down their arms on the Maytény plain, swearing an oath of allegiance to Joseph I, who was already dead.

Under the terms of the Peace of Szatmár, signed by 151 squad leaders, the rebels were granted amnesty, allowed to return home, and, if they were noble, to keep their former estates. This even applied to Rákóczi, who did not return to Hungary but went into exile to fight for the renewal of the War of Independence until he died in 1735.

In the Peace of Szatmár, after the death of Joseph I, Charles III, the Emperor promised to abolish foreign institutions that offended Hungarians, to convene a Diet, and to respect the liberties of Hungary and Transylvania. Rákóczi, who was in Poland, considered Károlyi’s action a betrayal and disdained the results achieved, but, taking a realistic view of the deal, Pálffy offered a very favourable peace despite the Habsburg superiority, against which war was no longer an acceptable alternative for the Kuruc forces.

The peace concluded in Szatmárnémeti finally ensured the country, exhausted by Turkish and Kuruc wars, a peaceful development during the 18th century, while preserving in Hungarian memory the romantic image of the prince in exile in a far-off land, fighting for the just cause to the end.

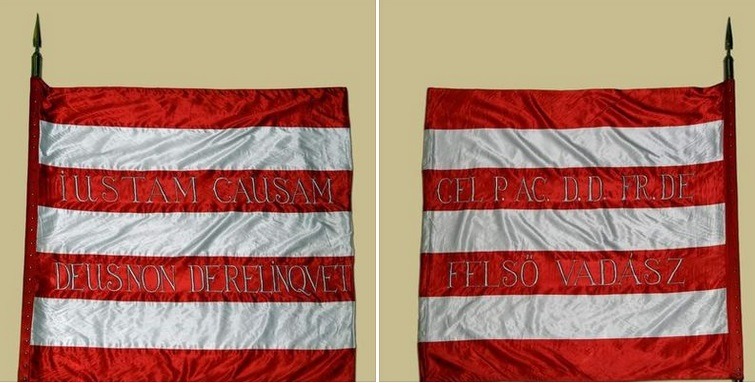

The contemporary records list between 147 and 182 flags, but there are several different figures on the number of flags handed over, and since two regiments of the Kuruc arrived late to Majtény, some of the differences may be due to the number of flags handed over later.

Sources: Rubikon Magazin (Tarján M. Tamás), Magyar Hadtörténeti Múzeum

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital. They are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! Donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfkn