The rebellious Bohemian nobles, allies of the Transylvanian prince Bethlen Gábor, were defeated near Prague at White Mountain on 8 November 1620. This left Prince Bethlen alone in the war against the Habsburgs. The Hungarian units that had fought at the Battle of the White Mountain returned home unscathed and with plenty of booties. They suffered very few casualties.

Let’s examine this battle from the Hungarian point of view, based on Roland Balogh’s article, “Did the Hungarians also contribute to the Czechs’ Mohács?”

Fourteen hundred and four years ago, the first major battle of the Thirty Years’ War, the Battle of White Mountain, was decided in less than two hours and had a decisive impact on the future of Bohemia.

Frederick Pfalz V was eating his lunch in Prague when the first refugees arrived from the White Mountains near the city to report that his troops and their Protestant Allies had lost the battle to the forces of the Habsburg Emperor Ferdinand II and the Catholic League after about two hours of fierce fighting.

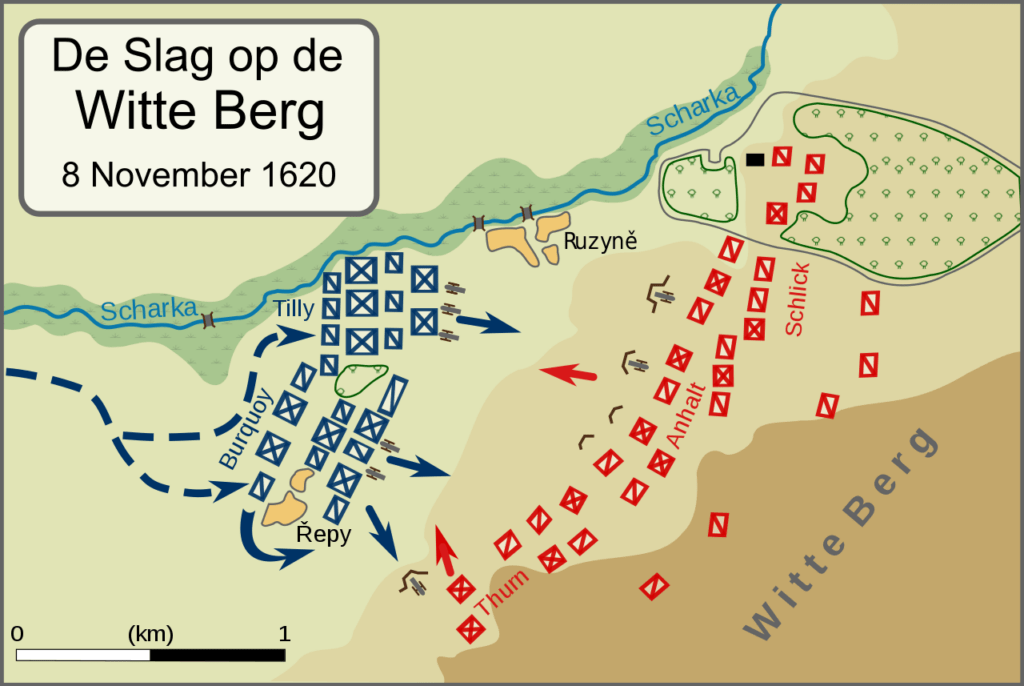

It was a very foggy Sunday morning on 8 November 1620. Frederick’s commander, Anhalti Keresztély, and the Czech Count Thurn had 11,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry, and the young king’s ally, the Transylvanian prince Bethlen Gábor, had also sent some 5,000 Hungarian and Transylvanian light cavalry to help the Czech rebels. The emperor’s commander, Bouquoy, Prince Maximilian of Bavaria, and General Tilly, who commanded the League troops, had about two thousand more men, including 17,000 infantrymen organized on the Spanish model and a Polish Cossack cavalry unit.

Although the Bohemians held the strategic advantage at the top of the ridge, Anhalt’s soldiers refused to dig in, saying that digging trenches was a peasant’s pastime. Frederick’s attempts to dig trenches were in vain, but by the time anything could have come of it, events had already swept his kingdom away. The fog helped the Imperials and the Bavarians, who Spaniards, Italians, and Walloons surrounded.

The regiment was in position at about eight o’clock in the morning, the ten guns of the Czechs, set up in a nearby ground sheltered by palisades, began firing, but they had little effect. The enemy’s dozens of guns began firing simultaneously 15 minutes after noon. Thurn’s horsemen dived down to the enemy, fired a volley from long range, and then fled. Anhalt’s son, seeing the confusion, stampeded into an Imperial entrenchment with his horsemen, his soldiers trying to reduce the infantry to pieces with pistols.

For a moment, it looked as if the Allies might win the battle, but Bouquoy, arriving on the scene and unconcerned about his previous serious wounds, broke the deadlock. Anhalot the Younger was captured, and the resistance lasted less than an hour. The lines of the Czechs and their allies were broken up, and the Hungarian and Transylvanian cavalrymen in the third line also fled. Schlick’s Moravian units held out on the right flank until half past one in the afternoon, but Tilly wiped them out too. Some survivors fought on the playing field for another half hour or so, but they had little hope left.

According to the story, the battle was decided in favor of the Catholics by a Carmelite monk who was fighting with the Bavarians. Domingo Ruzzola, of Aragonese origin, carried a hollow-eyed image of the Virgin Mary around between the Imperial and Bavarian troops, saying that this was what the Calvinist barbarians were doing with the holy images. According to the report, the destruction of the icon, which had been found three weeks earlier in a completely ruined house, had had its effect, inflaming the Catholic forces, who went after the Protestants, who were in a general low ebb in terms of troop morale, with even greater fervor.

The Allies lost 600 men on the battlefield, a thousand of them fleeing towards Prague, while 1200 were wounded. On the other side, some 650 dead and wounded were reported – most of them attributed to Anhalt the Younger.

This was quickly followed by a crushing defeat in the first, Czech phase of the Thirty Years’ War, which ended on 23 May 1618 with the infamous Second Prague Defenestration, the throwing of the leaders of the Habsburg administration out of the window. But how did Bethlen Gábor, perhaps one of the most sophisticated diplomats and tacticians of the age, get involved?

By having the Bohemian Protestant aristocrats, allied with the Austrian Protestant nobility, wield the Czech crown for him before Frederick. Even though the Transylvanian prince was a tried and tested veteran schemer who knew he didn’t stand much of a chance, it was still a pity that on 26 August 1619, the Electoral Prince of Pfalz was finally invited to the Prague throne.

Regardless of this, Bethlen stood up for the Bohemian rebels, as he seized the opportunity offered by the faltering power of the Habsburgs in Central Europe and focused on the more realistic Hungarian crown. Skilfully maneuvering between the Turkish Porte’s intricate political interest groups, by the autumn of 1619 he had conquered almost all of the Habsburg-ruled Hungarian royal territory, except for the Slavonic-Croatian parts. He brought the local nobility to his side and, not least through hard fighting, seized the Holy Crown, which was kept in Pozsony.

On 25 August 1620, the Diet of Besztercebánya elected him King of Hungary, but he did not risk being crowned because of the lack of adequate support from the Habsburgs, and in particular the lack of serious Turkish support, which he constantly requested through his envoys. He had already sent troops of cavalry to Frederick, as well as helping in the skirmishes between the Czech and Austrian Protestant Order rebels around Vienna. In his excellent summary of the history of the Thirty Years’ War, Peter Wilson also notes that both Bethlen and the rebels expected more from the other, so they never really swayed in the same direction.

A fascinating question is whether Bethlen ordered his generals to arrive late for the battle of White Mountain on purpose. According to the contemporary chronicler Georg Kraus, a Transylvanian Saxon who was fond of the prince and to whom he owed a great deal, he did. He wrote:

“[The Czechs] sent envoys to Bethlen Gábor, informing him of the day on which they would fight a decisive battle with the Imperials and the Bavarians, and that he should hasten to their aid. Bethlen Gábor was delighted at the news, for he took the matter to heart. He sent Chancellor Péchi Simon forward with 10,000 men, with orders to arrive at the White Hill, where the battle was to be fought, only an hour or two after the battle had begun; then he was to press forward and attack at once.”

But what happened? – According to the chronicler, Péchi was bribed by the Habsburgs and promised the Transylvanian principality, and betrayed Bethlen by not arriving at the battle, leaving the Czechs stranded.

But what is true of all this? The translator of Kraus, Vogel Sándor, also notes that the battle was fought with a Hungarian army of about five thousand men under the command of Bornemissza János and Kornis Zsigmond, while Péchi’s estimated three thousand men did not arrive. The latter’s intrigue was revealed, as Kraus recalls, and the Sublime Porta, who had deliberately dismissed Péchi from the Hungarian high command on White Mountain, later sent compromising letters to Bethlen to expose him.

The chancellor was arrested and imprisoned, but the prince spared his life, not least through the intervention of the Turks. Péchi was ransomed in 1624 for the equivalent of a year’s tribute that Transylvania would have been due to pay to the Turks. Because of his radical Sabbatical beliefs, even Bethlen’s successor, Rákóczi I György, launched a hunt for him, and he was sentenced with his daughter in 1638, but he was released from prison again, and died shortly afterwards, in 1640, outliving Bethlen by eleven years.

Kraus’s chronicle, which is surprisingly rich in its coverage of these events of the Thirty Years’ War, is thus only partially correct. Bethlen’s troops took part in the Battle of White Mountain, but we do not know what would have happened when if the extra three thousand Hungarians had arrived. What would the resulting Protestant overwhelming force of about a thousand have achieved? Probably not much. As we read in Wilson, the morale of the Hungarian troops was even weaker than that of the Czech and other Allied mercenaries who had been unpaid for months. It was not for nothing that the Hungarians were placed in the useless third line of rearguard, and in addition they fled immediately when the units in front of them took a rearguard action.

After the battle, Frederick’s reign, increasingly unpopular with Protestant Czechs because of his brash Calvinism and his destruction of images, collapsed in an instant. Later nicknamed the Winter King, the Elector of Pfalz fled to the Netherlands with his wife Elizabeth, daughter of King James I of England, and their children. According to the story, he feared that the angry Czechs would not let him leave the city if he took the crown and coronation jewels with him, so he ‘left’ them in the middle of Charles Bridge.

The Imperials brutally sacked Prague. The League of the Estates was dissolved, and the Bohemian resisters and Protestants, the leaders of the noble uprising and the cream of the intellectual elite were brutally executed, expelled and then recatriated from what had been a three-quarters Protestant country.

In a reorganisation of its administration, Bohemia was ‘downgraded’ to the level of an Austrian hereditary province, and German was made the official language – already used by many Bohemian noble families – instead of Czech. After the decimation of an already mixed political elite, control was handed over to even more dynastic aristocrats, in many cases resettled from other Habsburg-ruled regions.

One of the reasons given for the rapid defeat of the uprising is that it was the self-interested action of a narrow elite that did not seek to build a mass base. It was not about taking power into their own hands, rather than against German rule or the Habsburgs. In contrast to the Dutch or English parliamentary models of the time, the rebellion of the Bohemian Estates did not deny the institution of monarchy, but rather sought to transform it into an institutionalised aristocratic authoritarian system with a king without power (see the Polish noble republic), but failed to do so, and was defeated by the emerging absolutism.

After the battle, Bethlen was left in a vacuum. Following Ferdinand II’s clever tactics of pardoning the Protestant rebels in the Austrian provinces – only to force them to convert to Catholicism or leave the country shortly afterwards – the Hungarian lords were terrified of meeting the fate of the Czechs. So they began to desert the Transylvanian prince who had been elected Hungarian king.

For Bethlen, the Turkish support came too late, by then he was alone. Thus, the coronation remained an eternal dream, and the Treaty of Nikolsburg, signed on 31 December 1621, was signed by King Ferdinand II. In return, his supporters were granted amnesty, and he received seven Hungarian counties (Szabolcs, Szatmár, Ugocsa, Bereg, Zemplén, Borsod and Abaúj), for the maintenance of their fortresses he received 50,000 forints a year from the emperor, who also ceded the fortresses of Tokaj, Munkács and Ecsed to the prince.

And since the treaty confirmed the Treaty of Vienna of 1606, Ferdinand II also recognised the independence of Transylvania, the free exercise of religion by Protestants except in market towns, and the restoration of the religious self-government. In other words, Bethlen indirectly protected the Hungarian nobility from falling to the fate of the Bohemians.

The Hungarian proverb “Csehül állunk” (We are in a bad situation like the Czech”) was born this time

This refers to the events of the 1620s, when the outbreak of the 30 Years’ War began with the rebellion of the Bohemian nobility against the Habsburgs: we have already recalled these events.

Subsequently, the policy of retaliation was part of the Habsburg government’s policy. It was declared that the rebellion of the Estates against the Emperor was nothing more than a rebellion, and that Bohemia had been defeated by the Emperor at gunpoint, making it a conquered province. Moreover, since the lands of the Czech crown (in forma universitatis) have turned against their legitimate ruler, the monarch can quite legitimately deprive them of all their political freedoms and religious privileges. And they have no say in the making of new laws.

When, in 1627, Ferdinand II issued a decree regulating the succession to the Bohemian throne and authorising only the Catholic religion, he did not even talk about Bohemian estates, only about subjects (!). All this was done in the spirit of absolutism, in the spirit of the new times.

In Hungary, where the Habsburgs were the legitimate kings of the country and had already announced their claims to power in the difficult and confused period following the Battle of Mohács, the Viennese government also tried to find a way to centralise its ambitions. However, this met with resistance from the Hungarian nobility.

Already in the middle of the 16th century, centralised government bodies had been established, which took their decisions separately from the provincial governments of the estates, and were managed by a body of ‘specialists’ who received regular salaries from the state, thus the development of a state bureaucracy was under way. These included the Geheimer Rat (Privy Council), which acted as the supreme governing body of the Habsburg monarch, and the Hofkammer (Court Chamber), which managed the revenues of the treasury.

The Court Chancellery (Hofkanzlei), which handled diplomatic affairs and collected the taxes that were voted in. In 1556, the War Council (Hofkriegsrat) was set up to decide on military matters and to deal with all matters relating to them. However, while in the provinces of the Habsburg Empire the rulers had managed to govern the increasingly organised and well-organised state more or less smoothly by the new method of government, in Hungary the nobility saw these efforts as a violation of their constitutional laws. Under King Ferdinand I, the Council of Viceroy was created to represent the person of the monarch, and the Hungarian Chamber of Deputies – both headquartered in Pozsony (Pressburg, Presporok, Bratislava).

The ruler tried to bypass the Hungarian noble government, the Diet and the decisions of the noble counties through these governmental bodies. When in 1562 a prominent politician and military leader of the time, Nádasdy Tamás, the country’s Palatine, died, the Viennese government left this important office in the Hungarian constitution unfilled for forty-six years, and sought to curtail Hungarian constitutionalism by limiting the role of the Diets.

However, in order to propose and vote on taxes, it was necessary to convene the Diet, so the ruler could not bypass them, where the nobles always presented their grievances, and without redressing their grievances, they could even refuse to vote on taxes so important for the functioning of the state and military expenditure.

There is no doubt that the ruler had to exercise power in a shared way with the Hungarian nobility, but he had other ambitions in building a “well-organised state”. The interdependence of the Hungarian estates and the Habsburg government was clearly visible in the constant threat and conquest of the Turks.

Without the financial support of the Habsburg Empire, it would have been unthinkable to maintain the defence, since the revenues of the country, which was divided into three parts, could not have covered the considerable costs, while at the same time the well-established Hungarian and Croatian system of Borderland castles acted as a barrier against the daily waves of conquering attacks.

“In the Habsburg-ruled part of the Kingdom of Hungary, the institutions of the nobility were preserved: the Diet, the county organization, the principal dignitaries. The Hungarian Chancellery and the Hungarian Chamber were in principle independent of the central government bodies, but in practice they were relatively quickly subordinated to the administration of Vienna. In exchange for the organisation and financing of the common defence against the Turks, the Hungarian nobility were forced to relinquish their autonomous control over military, financial and foreign policy, but more importantly, they did not have a foothold in the central government bodies either.”

The conflict between the Habsburg power and the Hungarian Estates, however, became decisive in the following century, the beginning of the 17th century…

Sources: Szerecz Miklós and Balogh Roland

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts:

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital, they are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! and donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfkn