King Lajos I the Great (r.1342-1382)

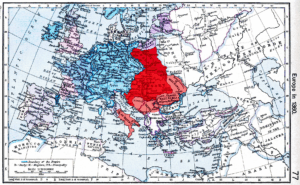

Looking at the pages of the Képes Krónika (Illuminated Chronicle, 1360) one might readily believe the legend that „three seas were washing the borders of Hungary during his reign”. (This is only true if we count the Mediterranean and the Adriatic Sea as separate ones; the third was the Black Sea.)

Family issues

After the death of his brothers, the young prince Lajos became even more of a focus of interest and could not be left out of his father’s dynastic plans. In 1338 he became engaged to Margit, the daughter of Charles Margrave of Moravia (later Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor) and his first wife, Bianka Valois, born in 1335. The marriage was intended to strengthen the hegemony of the Kingdom of Hungary in Central Europe and also to secure the support of the Bohemians in the event of the death of their son Casimir III (the Great) (1333-1370) without an heir, the Polish throne being placed under the jurisdiction of the King of Hungary.

According to the agreement concluded on March 1, Margit was to be accepted as Lajos’s wife, provided that “she does not suffer from any physical defect that would justify her being rejected by Lajos”. The future queen was to be placed at the court of her mother-in-law, Erzsébet, to familiarize her with the Hungarian language and customs. After the coronation of Lajos on August 3, 1342, it was decided to postpone the wedding, which had been scheduled for September 29, as Margit had not yet reached the legal age of marriage. The ceremony probably took place in 1345. Not much is known about the marriage of Lajos and Margit, and according to Küküllei János, the marriage with the “very beautiful” maiden was not blessed with children.

The queen died in the fall of 1349, most likely of the plague, although the sources are not clear. The widowed king soon married again. He married Erzsébet, the daughter of Stephen Kotromanić, a Bosnian king, and (related) Princess Elizabeth of Kujava (Poland). The Buda Wedding of 1353 was also world famous because it was the time when the wedding of Charles IV, the Holy Roman Emperor, and his third wife, Anna of Schweidnitz, took place.

The geographical location of Bosnia made Erzsébet, or rather the person of her father, very important for the king’s Balkan and anti-Venetian ambitions. In any case, it is interesting to note that Louis’ decision was probably influenced by the ‘love’ strand. For “some reason”, the fact was that Erzsébet, who had been brought up at the court of the widowed queen mother, had to be married so quickly that the couple could not ask the pope for a dispensation from their fourth degree of kinship (a canonical impediment to marriage).

According to Bertényi Iván, the reason for the haste may have been an unborn child, at least as evidenced by Pope Ince IV’s decree of August 31, 1353. King Lajos I and Erzsébet, daughter of King Stephen of Bosnia, despite their fourth-degree relationship, requested that the excommunication imposed on them by the Holy Father be lifted for the reasons given by him for their marriage and that they be given permission to marry posteriorly. To avoid a scandal, the pope ordered the recipients to release the king and Erzsébet from excommunication in due time and to allow them to marry so that there would be no doubt about the origin of the child born of the marriage.

This is the only information about the child mentioned in the bull, so he was most likely stillborn or died as an infant.

The royal couple did not have another child until 1370. Since the contemporary view was that it was the woman’s fault if she “failed” to produce a son, Erzsébet’s life could not have been easy anyway, and her strong-willed mother-in-law had a strong influence on the daily life of the court: the queen was hardly involved in national politics. In fact, according to the Italian historian Matteo Villani, the Pope was ready to separate the king from Erzsébet so that “his wife, who had seemed barren until then, could go to a convent of her own free will, and he could marry another woman so that the country would not be left without an heir of his own line”. But the king stood by his wife.

The desire for a child must have been strong, as suggested by the image of St. Catherine of Alexandria on the front page of the Illustrated Chronicle, with the royal couple kneeling before the Martyr. Some previous research has suggested that the monarch and his wife prayed to the martyr for the blessing of a child.

However, the succession to the Hungarian throne had to be secured. The closest to the throne of King Lajos I was a daughter of his brother István, (he died in 1354), and so a real race for Erzsébet’s hand began between potential candidates for the throne of the neighboring powers – the Luxembourg and the Habsburgs.

However, the Hungarian king wanted to prevent his immediate neighbors from claiming the throne, so in 1364 he brought to Hungary a member of the Anjou family of Naples, Charles of Durazzo (the Little), who was given the title of Slavonic prince, thus indicating to the public that he was the heir to the throne. Charles IV, however, made repeated offers of marriage and traveled to Buda in person at the end of November 1365 to arrange the betrothal of his son Wenceslas to Erzsébet. However, King Lajos I cut the intricate knots of the dynastic web almost at once.

At the beginning of 1370, Charles (Little) Durazzo married his own niece, Margit, and Erzsébet became the wife of another Neapolitan Angevin, Louis of Taranto, Emperor Emeritus of Constantinople. With these decisions, the King of Hungary made it clear to all that he wanted the succession to the throne to be exclusively within the family.

But then an unexpected event occurred: within a short time Erzsébet Kotromanić gave birth to three daughters. Katalin was born in 1370, Mária in 1371 and Hedvig in 1374. The daughters became, in the words of Csukovits Enikő, “the best-selling brides in Europe”. In 1374 Katalin became engaged to Louis, the younger son of Charles V (Valois) of France, later Duke of Orleans, and as a dowry, she claimed the throne of Naples.

Charles IV did not want to be left behind in the “battle” for her hand, and as early as 1372 he proposed that Prince Zsigmond, then four years old, should marry one of the daughters of King Lajos I. The planned engagement to the younger daughter, Mária, was confirmed by King Lajos on June 21, 1373. The papal dispensation was necessary in any case, as the children were related to each other in the fourth degree: Zsigmond’s mother, Elizabeth of Pomerania, was a cousin of Mária’s grandmother, Elizabeth of Piast. Two years later, on April 14, 1375, the Hungarian and Polish political elites again declared their support for the marriage. The betrothal took place four years later. The future of Hedvig, the youngest daughter, was very close to William of Habsburg.

The agreement concluded in Zólyom on February 12, 1380, between King Lajos I and his mother and wife and Prince Leopold III of Austria concerning the marriage of Lajos’s daughter Hedvig and Leopold’s son William of Habsburg. The birth of children also contributed to the stabilization of the position of Kotromanić Erzsébet, although the fact that her mother-in-law became an important actor in the Polish-Hungarian personal union of 1370, ruling her homeland as a governor, also played a role.

Elizabeth of Piast’s influence remained at the court throughout her life, so the relationship between the two queens could not always be smooth, although Elizabeth of Piast’s will of 1380 gave a prominent role to her daughter-in-law. On the one hand, she appointed her as one of the executors of the will, and on the other hand, she bequeathed to her a considerable inheritance – the castle of Óbuda, a plenarium depicting the Virgin Mary, a golden chalice, a breviary used by the queen.

The actions of the charter are also instructive for the grandchildren: Mary and Hedvig received sets of jewelry. The eldest daughter received a ten-piece wreath headdress, a clasp, a piece of jewelry to be worn under a veil, and two golden eagles. Hedvig was given a headdress with lilies and a jeweled clasp. Prince István’s daughter Erzsébet joined them in the will, and her grave was also well provided for (2,000 forints and 10 measures of purple).

For King Lajos, it was a very difficult problem to ensure the succession to the Hungarian throne through the female line because at that time only men (boys) could rule the country. In addition, the Polish-Hungarian personal union meant that the situation in our northern neighborhood was similar. The Polish nobility finally managed to accept the succession of the daughter branch by issuing the so-called Privilege of Kassa (1374), which granted several privileges – almost complete exemption from taxation, no appointment of foreigners to provincial offices, and the abolition of royal investiture.

The only male relative in question, Charles of Durazzo (Little), conquered the Kingdom of Naples with the support of the Emperor, who is said to have even persuaded the ambitious young man to be content with ruling the southern Italian country. In King Lajos’ vision, both of his kingdoms would be inherited by Mary, who was crowned on September 17.

However, the most important demand of the Poles – that the ruler should live in Krakow – could not be met, and the throne was taken by his sister Hedvig, who was crowned on October 16, 1384. The ceremony also marked the end of the Polish-Hungarian personal union. It was also a great personal sacrifice, as she had to break off her engagement to marry Ulászló Jagelló of Lithuania soon after.

Political issues

Photo: Kocsis Kadosa

After the death of King Lajos, Mária assumed the throne of the Kingdom of Hungary, but as she was a minor, her mother, Erzsébet Kotromanić, ruled the country. She felt that her time had come, but her unpredictable and indecisive decisions led to a breakdown of stability and antipathy towards her, leading to civil war. A woman cannot govern a fierce people, a weaker one cannot calm the war she has stirred up” – these were the words with which Bishop Horváti Pál of Zagreb invited King Charles Durazzo of Naples to the Hungarian throne. Despite his wife’s strong objections, Charles accepted the invitation and set off for the interior of the country.

The queens still hoped for some kind of compromise, but on December 31, 1385, Charles had himself crowned by Archbishop Demeter of Esztergom. Before the ceremony in Székesfehérvár, Erzsébet and Mária entered the tomb chapel of King Lajos. “When they saw the marble statue of the pious king, their hearts almost broke, and they kissed the sad picture for a long time, embraced the cold stone and flooded the red marble with a shower of tears. The effect was not lost on those present, who realized that they had gone completely against the will of the great king. The fate of the “sworn” Charles II (Little) was fulfilled on February 7, 1386, when he was seriously wounded by Forgách Balázs during an assassination attempt organized by the Palatine Prince Garai Miklós, and his life ended on February 24.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C0m3h-CM53Y&t=51s

Part Four: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5ZYNrxrhheI

Part Five: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5cPyDh-n2AU

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts:

Please, feel free to support me with a coffee here: You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital, they are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook: https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!