Let me share a gap-filling guest post, the work of Szilágyi Szilárd.

Avram Iancu, a National Hero or War Criminal?

This year, 2024, has been declared the Avram Iancu Memorial Year in Romania, with countless celebrations, processions, wreath-laying ceremonies, folk and military music, and many red-yellow-blue flags.

There is hardly a town in Transylvania that does not have a statue of him, or at least one street, square or institution that does not bear his name. His full-figured statue was erected on a tall stone column in Kolozsvár (Cluj) in December 1993, on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the Gyulafehérvár Assembly that declared the unification of Transylvania with Romania, on the square that today bears his name (formerly Bocskai).

In Marosvásárhely a statue of him on horseback was erected, while his bust was placed in the middle of the site of one of the most brutal massacres in Abrudbánya.

The parliamentary group of the National Liberal Party used to kneel and pray before his statue in the Romanian Parliament.

His portrait was printed on the Romanian banknote of the 5000 lei in 1992:

Today, two communes in Romania bear Avram Iancu’s name: one in his native village (Felsővidra) in Fehér (formerly Lower Fehér County), and the other (the former village of Keményfok) in Bihar County. The airport of Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca), the capital of Transylvania, is named after him. In 2023 a movie was made about him called Avram Iancu Against the Empire.

Today, Avram Iancu is considered one of the greatest national heroes, a part of the Romanian historical pantheon.

Why all this? He is the Romanian national hero, the revolutionary who fought against Hungarian oppression and defeated the Hungarians who wanted to suppress the Romanians’ fight for freedom. This is what you hear about him in Romania, this is how he is described and presented to the world. But to talk about the thousands of Hungarian civilians (women, children, babies alike) killed by him, his subalterns, and his troops, the dozens of villages and towns burned, the people left without anything, the hundreds of years old schools, libraries turned to ashes, is a taboo in Romania, and the Romanians do not know about it, because talking about all this is a taboo.

But let’s see who he was.

His early life

There are many myths and legends in the Romanian national consciousness. But who was he in reality? He was born in Vidra in 1824, the second child of peasant parents. His birth house:

His father was a wealthy serf, a forester of the state estate of Topánfalva.

Avram Iancu began his education in his village, then in 1837 he attended the secondary school in Zalatna, and between 1841 and 1844 he was an excellent student at the Piarist grammar school in Kolozsvár. He became acquainted with the Hungarian reformist politics in the atmosphere of the Transylvanian Diets of Kolozsvár. After 1844, as a law student, he expressed his hatred of the serf system with youthful enthusiasm and fervent revolutionary spirit.

The young jurist closely followed the debates of the 1846 Parliament and reacted with fervor to every reactionary attempt to delay the serf question. After graduating from the Law Academy in Kolozsvár, he went to Nagyszeben (Hermannstadt, Sibiu) as a civil servant, but here, in the capital of the Saxon self-government, a son of a serf had no chance of promotion. So he went to Marosvásárhely (Târgu Mures), the capital of the Székely Hungarians, where about 34 Romanian lawyers worked together with Hungarian lawyers from Transylvania.

Portrait of young Avram Iancu in Marosvásárhely:

Among them were many of his later comrades-in-arms, such as Alexandru Papiu-Ilarian, Amos Tordăşianu, Vasile Fodor, Ilie Măcelaru, Samuil Poruţiu and others. The Romanian and Hungarian lawyers enjoyed close friendship and cooperation, and the March 15, 1848 revolution in Pest inspired the young lawyers from Marosvásárhely.

The Hungarian revolution and the Romanians’ reason for the start of the Romanian revolt

The problems and misunderstandings began when Avram Iancu and the other Romanian intellectuals saw that in Hungary, as a result of the April Laws of the Hungarian Revolution, the serfs were liberated, while in Transylvania this did not happen immediately. Another problem was that the Romanians felt oppressed, they had no political representation in the Transylvanian Diet, they were not part of the so-called Unio Trium Nationum together with the Hungarians, Székelys, and Saxons, and therefore they demanded to be recognized as the fourth nation of Transylvania. They also demanded national and linguistic rights for the Romanians.

Therefore, their first national assembly was held in Balázsfalva (Blaj) in May 1848:

They declared that they were against the union of Transylvania with Hungary, which was one of the main goals of the Hungarian Revolution until their national demands were fulfilled. But they did not understand that the Union could solve their national and social demands most quickly!

First of all, the abolition of serfdom was part of the April Laws in Hungary, but before Transylvania was not united with Hungary, it was legally impossible to implement it in Transylvania. Therefore, it could only be enforced in Transylvania after the unification.

Second, the recognition of the Romanians as the “fourth nation” in Transylvania was impossible because the Hungarian Revolution put an end to the medieval-feudal concept of the nations of Transylvania, which were the “three nations” based not on ethnicity or common language, but on belonging to an aristocracy or a group of special status, such as the Saxons and the Székelys, although most of the Székelys had already lost their special status in the 16th century. Many of them became serfs, so we can say that these “three nations” lost most of their meaning and importance by 1848.

The revolution of 1848 brought the modern concept of nation, based on ethnicity and citizenship, abolishing the “three nations” of Transylvania and declaring that from now on all citizens of Hungary were equal, regardless of their ethnicity, mother tongue or religion, and that they were all part of the Hungarian nation, as in modern states. For example, in France, based on the same modern concept of nation, there is no British, Basque, or German nation, but only the French political nation, or in Romania, Hungarians are still not recognized as a nation, but as a minority.

Also in Hungary, from 1848, there was only the Hungarian nation and no other nation could be accepted because it would mean the partition of the country. The people of other ethnicities were recognized as different ethnic groups that could freely keep and develop their language and culture, but they were not recognized as nations but as nationalities.

Thus, Hungary, which abolished the “3 nations” of Transylvania based on the modern concept of a nation, could not establish a new one, the Romanian one. But, as Hungarian citizens, they had the guarantee that all their language and nationality rights would be respected.

Third, the Romanians demanded national and linguistic rights. Some of the Hungarian politicians were afraid of this, fearing that it could break Hungary apart, but already at the end of August 1848, the Hungarian political class was ready to implement very important rights for the Romanians and the other nationalities. After the elections of July 1848, there were many Romanian representatives in the Hungarian Parliament, with whose help the Union Commission of the Parliament prepared a draft law on nationality, which gave very important rights to the Romanians. These rights were the following:

- It allowed the use of the Romanian language in primary and secondary schools, seminaries, and church administration.

- In Romanian-speaking villages and parishes, it recommended that records be kept in both Romanian and Hungarian, while only Hungarian was stipulated for correspondence with other authorities.

- In the Counties, Seats, and Cities inhabited by Romanians, it allowed them to speak in Romanian in the official councils and assemblies.

- The language of command of the National Guard would be Romanian, in addition to Hungarian.

- Laws and royal and ministerial decrees would also be published in Romanian.

- Official documents, applications, and petitions written in the Romanian language would have to be accepted everywhere.

- Even Romanians who could not speak Hungarian, but only understood it, could be elected to the county assemblies and commissions.

- Administrators of the Romanian language, paid by the state, would be employed at the Royal Courts of Justice for the free representation of the poor people of the Romanian tongue.

- Romanians were to be employed in a “fair proportion” in all areas of public administration.

- It promised to abolish Transylvanian acts and laws that were detrimental to Romanians.

- Regarding education, the bill promised that the Romanian-speaking population would be taken into account in the establishment of public schools.

- A department of Romanian philology and literature would be established at the university. You can read more about it here: https://epa.oszk.hu/00400/00463/00005/pdf/152_katus.pdf pp 159-160 The fact that the Romanians joined the Austrian troops against the Hungarians, even though they were informed about this bill, and the fact that the Emperor dissolved the Hungarian Batthyány government and the Parliament had to deal with war issues, implemented this bill pointless for the time being, but also impossible. However, the Nationalities Act was finally passed and implemented by the second Hungarian government, the Szemere government, on July 28, 1849.

Another proof of the Hungarian goodwill was that the Hungarian money (called Kossuth bankó) issued by Lajos Kossuth, the then Minister of Finance, had German, Slovakian, Serbo-Croatian, and Romanian inscriptions (with Cyrillic letters).

If we study all this carefully, we can see that even today there are very few countries in the world that grant such important rights to national minorities. For example, if we summarize the points concerning the Romanian language, we can conclude that Romanian was practically recognized as an official language in the regions where the Romanians lived.

Today, in Transylvania, for example, Hungarians can only dream that the language of police and military units, official documents, and petitions will be in Hungarian, or that Romanian money will have Hungarian inscriptions. It is also a requirement that the Hungarian representatives in the local and national legislative forums be able to speak Romanian.

It is noteworthy that the leaders of the Romanians from Transylvania were aware of the very generous nationality law. In early October, after Timotei Cipariu had reported to him on the developments in Pest, Nicolae Bălăşescu wrote to George Bariţ: “We will get everything we want from the Emperor. But I want you to know that the Hungarian Parliament in Pest has granted us all the attributes of nationality”.

Read more about it here: https://mek.oszk.hu/03400/03407/html/369.html

The Romanians rejected the Hungarian proposals and sided with the Habsburgs against the Hungarians, starting with the October revolt of the commander of the troops in Transylvania (composed mostly of foreign and ethnic Romanian soldiers), Lieutenant General Anton Puchner, who declared himself loyal to the Emperor and enemy of the Hungarian government. They allied with him and the counter-revolution led and organized by the Habsburgs.

This was the beginning of the civil war in Transylvania, during which the Hungarians, especially in Western Transylvania, were attacked by large Romanian armed militias, allegedly organized by Avram Iancu and his subalterns in legions and cohorts, and threatened them with extermination.

From the very beginning of the Romanian movement, it was clear that the Romanians did not want only national rights from the Hungarians. In April and May, Vienna flooded Transylvania with pamphlets and agitators against the Union of Hungary and Transylvania, encouraging the Romanians to unite with the Saxons against Hungarian interests in exchange for the promise of the establishment of a Dacian Republic stretching from the Tisza to the Prut.

The radical spokesman of the Romanian National Movement, Simion Bărnuţiu, declared: “Every morsel taken from the table of Hungarian freedom is poisoned”. In his speech, he argued that “the Union is life for the Hungarians, death for the Romanians. […] If there is no Union, the link between the Hungarians of Transylvania and Pannonia will be broken, and the Hungarians of Transylvania will, of course, slowly disappear”.

(Source: Hermann Róbert: Az 1848-49. évi forradalom és szabadságharc története. Videópont, Budapest 1996. pp. 79-81)

So we can see here that, apart from the demand for rights, which is perfectly understandable, the Romanian leaders wanted to create a greater Romania, which would also include Transylvania and Eastern Hungary, and from which they hoped that the Hungarians would disappear in time.

Given these Romanian plans and hopes, it is quite understandable why the Hungarian gestures and the rights offered by the draft of the Nationality Law were rejected. In the events of that time, the Romanians saw an opportunity to realize their long-cherished dream: A Greater Romania where only Romanians will live and Hungarians will disappear! And they did not care how many human lives it might cost.

Romanian revolution or counter-revolution?

At this point we can ask: Were the Romanians from Transylvania who revolted against Hungary revolutionaries, as the Romanians claim? How can someone who revolts against a revolution and allies himself with the counterrevolution call himself a revolutionary? Counter-revolutionary, yes; revolutionary, no.

We can ask again: were there any Romanian revolutionaries in the Kingdom of Hungary in 1848-1849? And we can answer: yes!

Contrary to the narrative that all Romanians fought against the Hungarians, half of the Romanians living in the Carpathian Basin fought with the Hungarians against the Habsburgs. While the Romanians from Transylvania fought against Hungary, the Romanians living outside the territory of the Principality of Transylvania (the regions of Bánság, Partium, and Máramaros) supported the Hungarian Revolution from the beginning to the end and fought in the Hungarian armies against the Habsburgs, then also against the Russians in the last months of the Hungarian struggle for freedom.

There were several battalions in the Hungarian army made up entirely of Romanians who fought very bravely against the enemy. Nevertheless, the Romanian historical narrative is silent about them, claiming that all Romanians fought against Hungary.

Read more about this here: https://prominoritate.hu/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Nyar-Magyar.pdf

The civil war and the atrocities

When the numerically inferior Hungarian troops were driven out of Transylvania in October and November 1848, the war of extermination spread throughout the province. As they occupied town after town, the Austrian officers sent the Romanian militias to “disarm” the Hungarian inhabitants, and the Romanians took the opportunity to massacre often entire towns and villages where Hungarians lived.

In the settlements where there were also Romanians and Germans, only the Hungarians were massacred. Thousands died, subjected to various, well thought-out tortures (for example, babies torn from their mothers’ wombs, men cut to pieces and then their families put to eat their flesh, etc.) under the eyes of the Austrians, who did almost nothing to stop them.

Gradually, Avram Iancu became the supreme leader of these militias, and after the successful counterattack of the Hungarian army led by General József Bem and the defeat and expulsion of the Austro-Russian troops from Transylvania in March 1849, he also became the leader of the resistance of the Romanians in the Western Carpathians (called Erdélyi Középhegység in Hungarian and Muntii Apuseni in Romanian) against the Hungarians.

And now let’s see in detail what the Romanian militias did in Transylvania. Then we will discuss whether Avram Iancu’s resistance was such a great military achievement, a David-and-Goliath-like struggle, deserving of the great celebration and cult that exists around him in Romania today.

Before the outbreak of the civil war, there were two confrontations between the Romanian peasants and the Székely-Hungarian soldiers, which caused a great uproar among the Romanians and fueled their desire for revenge against the Hungarians.

Some Romanian serfs had occupied a part of the Esterházy Counts’ land, referring to the law on the liberation of serfs and the division of the nobles’ estates. The problem was that the way of division among the peasants and the compensation of the counts had not yet been decided, so the occupation of this land was illegal. The count called in the military as an executive power to enforce the law.

On June 2, 1848, about 3000 Romanian villagers became aggressive and refused to let the Székely soldiers enter the village. The situation continued to deteriorate, the peasants became more aggressive, and at one point a Romanian shot and killed a Székely soldier. The soldiers responded with a volley, killing 12 Romanian peasants and wounding 9.

The Romanian political organization, the Romanian Committee, investigated the events to find out who had started the hostilities. One of the Orthodox priests blamed some Romanian youths, saying that they had misled the peasants and incited them against the soldiers.

Avram Iancu, who was sitting in the back of the meeting room, immediately jumped up, grabbed the old priest, and scolded him violently. Then he is said to have stated: “Even the children of the Hungarians will weep for this.” It was probably at this point that he decided to arm the Romanian peasants.

Avram Iancu did indeed arm the people of Topánfalva on June 9. During the summer, arbitrary land seizures of peasants began.

After the declaration of Transylvania’s Union with Hungary, the conscription law was also enforced in Transylvania, but the Romanian peasants resisted. On September 12, the Székely troops were ordered against the peasants of Aranyoslóna who refused to register in the army, declaring that they did not want to obey the Hungarian government, but the Emperor.

In the end, the Székely soldiers fired on the aggressively approaching peasants, killing 13 of them. Interestingly, the Székely soldiers were sent to both Mihálcfalva and Aranyoslóna by the same Anton Puchner, the leader of the army in Transylvania, who after a month would declare his rebellion and ally himself with Avram Iancu and the other Romanian leaders against the Hungarians.

He could have chosen military units of other nationalities from his multiethnic army, but he sent the Székely soldiers against the Romanian peasants in June and September, most likely to stir up hostility and ethnic hatred between the Romanians and Hungarians.

The situation in Transylvania quickly spiraled out of control. The Second Romanian National Meeting in Balázsfalva on September 25 declared that they would not accept the Transylvanian-Hungarian Union or the Hungarian Ministry and that they would obey only the Emperor. The Romanian peasants were armed and began a general uprising against the Hungarian authorities. Transylvania drifted irreversibly toward civil war.

On one side, the Austrian armies under Lieutenant General Anton Puchner, the Romanian border regiments of Naszód and Orlát under Colonel Karl Urban, the Saxon people, and the armed Romanian peasantry – on the other side, the Hungarian, German, and Armenian population of some towns, the Hungarian diaspora of the counties and the Szeklers, the latter being the only significant Hungarian military force in Transylvania.

As the scattered Hungarian units were driven out of Transylvania, the massacres of the Hungarian population in the towns and villages began in October 1848.

Most of the killings began when the Austrian officers asked the Romanian troops to collect the weapons of the Hungarians in the occupied Hungarian settlements. The Romanian troops used this as an excuse to massacre or exterminate the Hungarian population of many of these settlements.

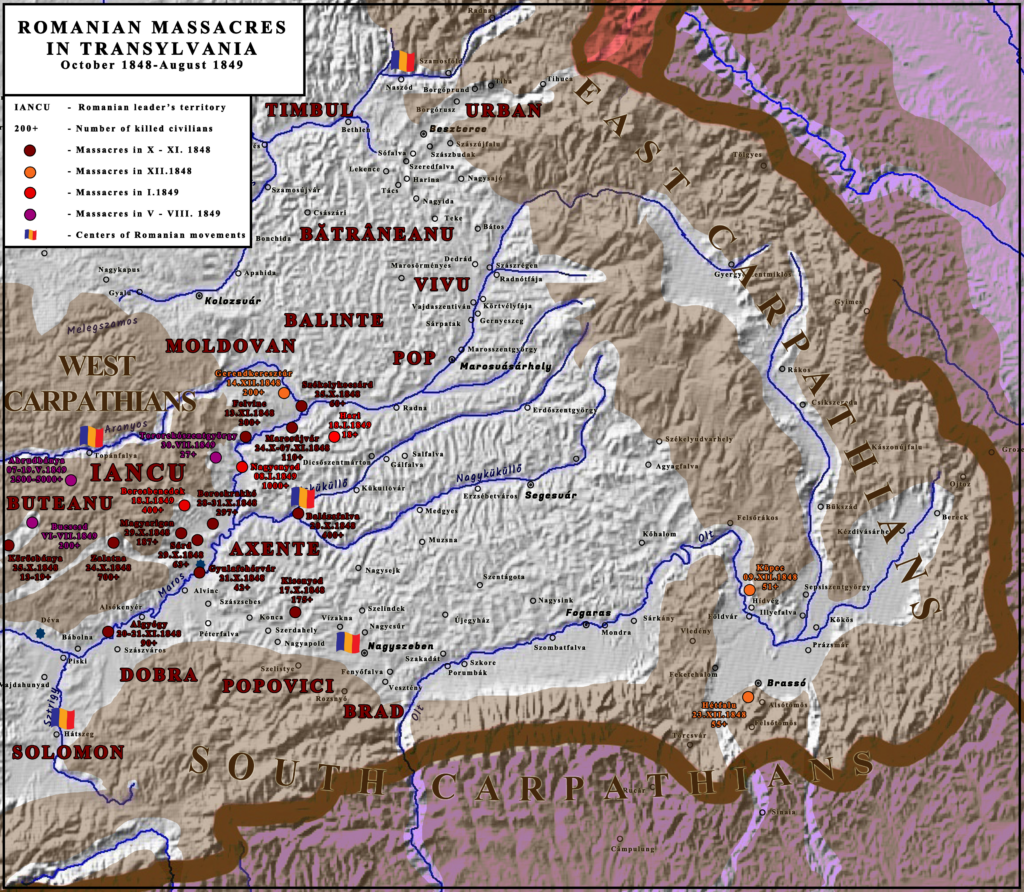

A long list of massacres took place in October and November 1848, during the fight for Transylvania against the imperial and Hungarian troops (I will write the Hungarian name of the place, followed by the Romanian name and the number of Hungarians killed):

Algyógy (Geoagiu) – 90, Borosbocsárd – 73, Diód (Stremț) – 25, Gyulafehérvár (Alba Iulia) – 42, Székelykocsárd (Lunca Mureșului) – 60, Hátszeg (Hațeg) – 15, Marosújvár (Ocna Mureș) – 90, Mikeszásza (Micăsasa) – 150, Kisenyed (Sângătin) -140-175, Zalatna (Zlatna) – 700, Magyarigen (Ighiu) – 200, Boklya (Bochia) – 30, Felvinc (Unirea) – 200, etc.

As an example, we can mention the massacre of the Hungarians of Zalatna. On October 22, the Romanian army of Avram Iancu and Dobra marched on Zalatna, disarmed the inhabitants, set the town on fire, and sent them on their way to Gyulafehervár. However, they attacked them in Ompolypreszáka and killed most of them (some say 700, others say 1000), men, women, and children alike. The dead were piled up and three mounds were built over them. Only 140 people survived. Contemporary picture of the Zalatna massacre:

Another tragic event was the massacre of the Brády family on October 25th. This noble family was of Romanian origin, but during the centuries until 1848, they became Hungarians, felt the danger that threatened them, and tried to flee from Brád, where they lived. But they were caught by a Romanian troop who ordered them to turn back because “the Romanian revolution is clean and they have nothing to fear”.

On the way back, they were stopped by a large group of Móc Romanians who began to rob them of their belongings, and at one point a Romanian peasant whispered to a woman from the Brády family that she should flee with her children to his house on the mountain. She did so with three of her daughters.

When a Romanian Greek Catholic priest began to ask the Romanians to spare their lives, he was stripped naked and tortured. Then the members of the Brády family (some say 13, others say 19) were massacred one by one, men, women, and children alike. The head of the family was hacked to pieces with axes.

Then they were thrown into graves. According to the records, one of the victims was Pál Brády (whose 1.5-year-old girl was thrown into the grave alive), a schoolmate of Iancu’s who often mourned him in his last years, when he was mentally disturbed. Perhaps because of his friend Pál, Iancu allegedly did not want the Brády family to be killed and sent an envoy to prevent the tragedy, but one of his subalterns, Axente Sever (who later became infamous for the Nagyenyed massacre), delayed him so that he arrived only after all the Brádys were dead.

This event inspired the writer Mór Jókai, who wrote a short story about the massacre of the Brády family entitled A Brády család (The Brády Family), in which he presents Iancu (called Decurion Numa in the story) as an idealistic leader fighting for the Romanian nation, but who, disgusted by the massacre of the Brády family by his troops and the death of his secret love, Jolánka Brády, whom he tried in vain to save, blows up his house, killing himself and his Romanian fighters who took part in the massacre.

These massacres took place mainly in the counties of Hunyad, Alsó Fehér, and Aranyos in Western Transylvania, where Iancu’s troops were active. In the other counties, where other Romanian militia leaders were active (Northern, Central, and Eastern Transylvania), there were much fewer atrocities against the Hungarians. This answers the question of whether or not Iancu was guilty of the massacres.

It seems that after a while even the Austrian command had enough of the massacres and ordered Iancu and his subalterns to stop them. So for most of November, these actions ceased.

But when the resistance of the Székelys of Háromszék began at the end of November, two other massacres took place, but they had nothing to do with Avram Iancu because they happened in southeastern Transylvania, where he was not active.

On December 9, after the Austrian troops had defeated the Székelys at Hídvég, their Romanian auxiliaries plundered the village of Köpec, killing 51 Székely villagers, among them a retired K.u.K. officer in the imperial army. Then, on December 23, they entered the town of Hétfalu and killed 55 Hungarians. But Iancu’s men were not resting on their laurels, and on December 14 they killed 200 Hungarians in Gerendkeresztúr.

But when the Hungarian army of Transylvania, led by General József Bem, began its successful campaign against the Austrian troops and gradually started to push them out of Transylvania, the anti-Hungarian massacres in Western Transylvania resumed, probably because of the frustration caused by the defeats and the perspective of the final Hungarian victory in this province. On January 8, 1849, the Hungarian population of Nagyenyed (about 1000 people) was slaughtered.

Many died at the hands of the Romanian peasants, led by one of Iancu’s most important subalterns, Axente Sever. Among them were the mother, brothers, and sisters of Africa’s first future female researcher, Sass Flóra, who became known as Florence Baker.

Flóra escaped only because the Romanian nanny of her family told the Romanian peasants that she was her daughter, so the Romanians did not kill her, believing that she was not Hungarian. Those Hungarians who were not killed in Nagyenyed died because they were driven out in the cold winter by the Romanians who burned the town and they froze to death. The plaque commemorating the Nagyenyed massacre:

The 300-year-old Calvinist College (Gábor Bethlen College) of the town was also burnt, together with the priceless ancient and medieval codexes and manuscripts. The picture of the college after its destruction:

And, believe it or not, in Nagyenyed (Aiud), the leader of the massacre of the Hungarian population, Axente Sever, has a school named after him and a statue of him at the entrance:

On January 15, Alsójára (Iara) was attacked by the Romanians, killing 150 civilians, and a few days later Borosbenedek (Benic) and Hari (Heria) were attacked, killing a total of 418 civilians.

After the battle, both in Vízakna (February 4, 1849) and the next day, the Austrians and the Romanian troops fighting with them slaughtered the wounded Hungarian soldiers or those who survived the battle and tried to hide in the houses or salt mines near the town. Most of the 50 wounded Hungarian soldiers sent from Vízakna to Szászsebes were killed by the Saxon rebels.

After the above-mentioned battle, 300 dead and still living wounded soldiers were thrown into the salt mines of Vízakna, where their bodies were found in 1894, preserved intact by the salt. Picture: Dr. Henrik König dissected the body of a “honvéd” (soldier) preserved in the salt mines of Vízakna.

On August 10, 1896, a marble monument was erected at the salt mine where the bodies were found as a tribute to the victims, but in 1920, after the Treaty of Trianon, the Romanian authorities newly installed in Transylvania demolished this monument. Not only the Hungarian soldiers were victims of the atrocities of the Austrian soldiers and the Romanian and Saxon insurgents, but also the Hungarian inhabitants of the town. Puchner allowed his soldiers 2 hours of free plundering among the Hungarians, but the plundering continued during the night.

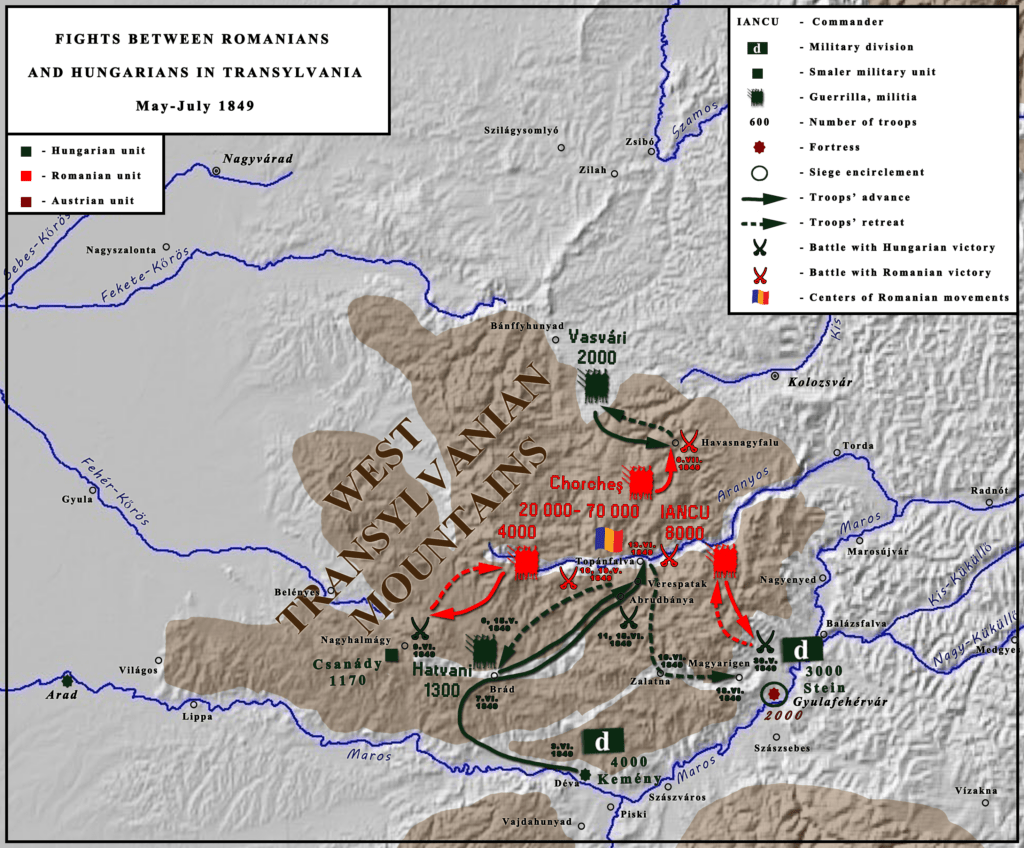

In February and March, however, the Austrian troops under Anton Puchner and the Russian auxiliaries under Grigory Skaryatin were decisively defeated in the battles of Piski and Nagyszeben. Thanks to them, the imperial and Russian troops were chased into Wallachia, and the Romanian militias led by Avram Iancu retreated to the Western Transylvanian Mountains, which became their impregnable fortress. Now the mountains were encircled by Hungarian troops, preventing any attacks on the villages and towns.

In this way, the lives of Hungarian civilians were saved for a while. The mountains were surrounded not by professional Hungarian troops, but by militias with inferior weapons, which were not enough to make their encirclement impenetrable, so Iancu was able to obtain weapons and supplies from the Austrian fortress of Gyulafehérvár.

In March and April, these troops, led by Major Kálmán Csutak, managed to push the Romanian militia of Avram Iancu further into the mountains, capturing many of their strongholds and defeating them in several battles. He also tried to reach an agreement and a ceasefire with the Romanians.

In this situation, the Romanian members of the Hungarian Parliament also tried to do something for the Hungarian-Romanian reconciliation. Ioan Dragoș, deputy from Bihar County, led the delegation. He probably met on April 23 with Iancu, Buteanu, and Dobra, the leaders of the Romanian rebels in the mountains, called Mócok (Moții). At the meeting in Mihelény, an eight-day cease-fire was agreed upon.

However, the reconciliation plan was thwarted when Imre Hatvani, the guerrilla leader, was promoted to the head of the troops defending the mining town of Abrudbánya, and he arrived in the town with his army of about 1000 men around 9-10 p.m. on May 6. Here is the picture of Abrudbánya before the fighting:

Meanwhile, the member of parliament Dragoș did not give up his conciliatory work. He wrote letters to Iancu, urging him to continue the talks, to which he received a discouraging reply: he wanted to negotiate only with “armed hands” from now on.

On May 7, thousands of Romanian troops led by Avram Iancu attacked Verespatak, forcing the small Hungarian garrison to retreat to Abrudbánya. The Hungarian inhabitants of Verespatak and the Hungarian miners living in the surrounding villages were massacred. Those who escaped hid in the mines, but after several days they were forced to come out by the hunger and the promises of the Romanians that they would be spared, but then they were murdered.

The Romanians also attacked Abrudbánya, and the vastly outnumbered Hatvani, seeing that his troops were running out of bullets, decided to retreat. Many Hungarians from Abrudbánya joined him, knowing that the Romanians would kill them all if they stayed in their town.

But when their wagons got stuck in the mountain passes, they could not continue and returned to Abrudbánya, where the Romanians massacred them, killing the Catholic and Unitarian priests as well. Dragoș, the Romanian deputy who tried to reconcile the two nations, was also killed by the Romanians of Iancu, who considered him a traitor. Abrudbánya after the massacre:

Hatvani fled with most of his troops. But then, after receiving some troops on May 17, he returned to Abrudbánya, which he found in ruins, and tried to gather the remaining Hungarian civilians and save them. But Avram Iancu attacked again, and he, together with the remaining Hungarians of the town and the Hungarians from the surrounding area, mostly women and children, started their death march again.

In the valley of Bucsony, the Romanians cut their way and Hatvani could escape only with his armed men, but the carriages with the civilians, women, and children were attacked and all of them were butchered. It is reported that 2500 Hungarian civilians died in the two massacres of Abrudbánya, while other sources speak of 5000 victims. Iancu’s men showed no mercy. Here is a book about the massacre with a picture of the slaughter on the cover:

In June 1849, the Russian army entered Transylvania and every military unit had to be sent against them. Now the mountains were no longer encircled, and the Romanian troops began to attack the undefended Hungarian towns and villages again, killing hundreds of people.

Then, at the end of July, with the help of the Romanian revolutionist from Wallachia, Nicolae Balcescu, who spoke with Lajos Kossuth, the Nationality Law was passed. Balcescu met with Iancu and they agreed that he would stop the attacks against the Hungarians. Nevertheless, many Romanian mobs continued their killings in August 1849.

For example, on July 30 a Romanian militia of several thousand men approached Torockószentgyörgy. The village sent 7 envoys to ask them to spare the population. But they were slaughtered. The villagers then fled to the mountains, but still, 20 of the stragglers were killed by the Romanians.

The village was then looted and burned. If the inhabitants had not fled, the number of victims would have been not only 27, but the Romanians would probably have killed them all. On August 16, in Buttyin, Mária Madách, sister of the greatest Hungarian playwright, Imre Madách, was captured by the Romanian peasants together with her teenage son and her husband and mercilessly murdered. Their bodies were reportedly thrown to pigs and eaten by them.

Finally, the Russian occupying army stopped these massacres. The commanders of the Russian troops, horrified by the crimes and slaughters, ordered them to stop and threatened the leaders of the Romanian troops with execution. This is how the Romanians finally stopped massacring the Hungarians.

The English agriculturist and author John Paget, who settled in Transylvania and lived there during the Hungarian Revolution, wrote the following in his book:

“The triumphal entry of the Romanian mob was greeted with great sadness, whose leaders, Avram Iancu, Moga, Micaş, and others, rode with Colonel Urban and a whole army of imperial officers. They were the murderers of the unarmed Hungarians and the robbers of the Hungarian towns and villages, which [they] only distinguished in this way”.

Or:

“An army of 15,000 men under the command of Iancu was camped between the burnt Felvinc and Torda, almost 10 miles away, while another army of 10,000 men under Micas appeared near the village of Szászegerbegy, only a few miles from the others. A group of Romanians surrounded the village, captured all the adult Hungarians, 120 peaceful people who had not harmed anyone, and – convinced, allegedly, by the Romanian priest – tied them up and herded them to the edge of the village, where they were murdered one by one in cold blood.”

(Author’s note: I found only the Hungarian translations of these two passages, so I retranslated these parts)

To this day, the Romanian side has not apologized for the massacres committed against the Hungarians in 1848-1849. Moreover, after the annexation of Transylvania to Romania in 1920, many of the monuments of the slaughter of 1848-49 were destroyed or removed. This was an attempt to erase the memory of the events. From then on it was forbidden to talk about them, and Avram Iancu and the other Romanian leaders who led them were presented as great heroes, but their gruesome actions against the Hungarian civilians are not mentioned at all.

About the total number of Hungarian unarmed civilians, old people, women, and children killed by the Romanians led by Avram Iancu and his subalterns. It is not an exact record. It is very difficult because the villages and parishes where the records of the inhabitants were kept were burned and destroyed.

After the defeat of the Hungarian Revolution, the Austrian Empire, which reestablished its rule over Transylvania, was not interested in researching and showing the destruction caused by its Romanian allies, with the knowledge and encouragement of the imperial officers and the Saxon German inhabitants, so that 18 years passed without this being researched on the spot. It is therefore impossible to establish an exact figure.

The Austrians kept a record of the victims of attacks and massacres, but with great exaggeration, they counted only those killed by the Hungarians. As a result, the exact number of Hungarian victims is difficult to determine. The Transylvanian historian Ákos Egyed believes that between 7500 and 8500 Hungarian civilians perished, while only if we look at the number of 2500-5000 killed in and around Abrudbánya alone, we can assume that there were many more.

We cannot pass by without mentioning the Romanian or Saxon victims of the Hungarian reprisals. Especially after the Hungarian troops recaptured Transylvania, the authorities tried to find and punish the culprits of the anti-Hungarian massacres between October 1848 and January 1849.

Unfortunately, the search for the participants and instigators of the atrocities often degenerated into a vendetta against innocent Romanians, especially when those involved in the search for the criminals were people who had lost family members in the massacres committed by the Romanians. So-called blood tribunals were set up to try and convict those found guilty of the massacres. According to the count of the Austrian authorities, there were about 4366 Romanian victims.

The total loss of population in Transylvania was estimated at 18,000 by Eduard Albert Bielz in his 1857 Handbook of Geography. According to his work, also based on official statistics, 6112 people fell victim to Hungarian reprisals (between 1851 and 1857, the imperial authorities found another 1278 executed persons, without mentioning their nationality). Of these, 449 were executed based on the verdicts of Hungarian fast-track courts, and 769 on the orders of officers, without formal verdicts.

The most notorious of these was the execution of the Saxon priest Stefan Ludwigh Roth, who was accused of inciting the Romanian peasants to revolt and providing them with weapons. After his execution, General József Bem, with the consent of Kossuth, gave the order to close the summary courts.

During the occupation of certain localities, 31 people were hanged, 709 were shot, and 2871 were killed in other ways. 1283 civilians were killed in military clashes. Of the 6112 people killed, 5,680 were men, 363 were women and 69 were children. By nationality, 5,405 were Romanians, 310 Saxons, 304 Hungarians and 93 others.

Read more about it here: http://konfliktuskutato.hu/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=154:etnikai-polgarhaboru-erdelyben-1848-1849-ben-&catid=15:tanulmanyok

The Romanian historian George Baritiu, who was an active participant in the Romanian movement in 1848-49, wrote that about 6000 Romanians died, and he rejected the highly exaggerated Romanian claims that 40,000 were killed. He said that if the Hungarians killed 40,000 Romanians, then the Romanians killed 100,000 Hungarians. So he knew very well the proportions of the civilian losses of both communities. So, if this is correct and the number of Romanian victims was 6000, then the Hungarians lost about 13,000-14,000 people.

Taking into account the losses of the two communities, we also compare the number of Hungarians and Romanians living in Transylvania at that time. The first accurate census in Transylvania was conducted in 1850. According to it, there were 1,226,998 Romanians (59.5% of the population) and 535,888 Hungarians (26% of the population) in Transylvania in 1850.

More about it: https://mek.oszk.hu/00900/00983/pdf/emnyar.pdf, pp. 21

This shows that the losses of the Hungarians, in terms of the numbers of the two ethnic groups, are much, much higher than it would appear from the number of victims alone.

We have to conclude that Avram Iancu and other Romanian leaders are guilty in:

- The launching of the civil war, in which both Hungarians and Romanians fell victim, because, as we have shown above, the Hungarians promised the Romanians great rights, many of which Romania still refuses to grant to the Hungarian minority in Transylvania or Moldavia (where even today the Csángó Hungarians cannot study in Hungarian in school, and even in church the masses are held only in Romanian). But for Avram Iancu and others, these rights were not enough. The Romanians, among whom Avram Iancu was the leader who wanted a military solution to the conflict and who started arming the Romanian peasants and leading them in actions against the Hungarians, were guilty of most of the massacres. Based on the very generous Nationality Law project of August 1848, all the massacres and destruction could have been avoided, but Avram Iancu and the Romanian leaders decided to ally themselves with the Austrians, hoping that Transylvania would be all theirs and that they could create a union between Transylvania, Moldavia, and Wallachia, thus creating a united Romanian state. For this project, they sacrificed the lives of thousands and thousands of innocent Hungarians, Romanians, Saxons, and other people.

- The region where he was the leader of the Romanian troops (Western Transylvania), was the place where most of the Hungarian civilians were killed, most of the localities were destroyed and burned, and most of the people remained without a home and became refugees. Although there were Romanian legions operating in all regions of Transylvania, 90% of the killings, plundering, etc. took place in its western counties (Alsó Fehér, Torda, and Hunyad) in the Western Transylvanian Mountains and around them, the center of the Móc Romanians, whose leader was Avram Iancu.

- He did not punish any of his subordinates or soldiers who killed, raped, and plundered, and he did not try in any way to stop these atrocities. The fact that almost all the atrocities occurred in the regions under his command shows that not only did he not try to stop them, but on the contrary, he encouraged them! Even after he supposedly agreed to a cease-fire with the Hungarians, the massacres continued, again around the Western Transylvanian Mountains, where Iancu had his headquarters. Was he such a weak leader that he could not keep his men under control? Or did he not care whether they killed innocent civilians or not? As we saw in the case of Brády Pál, he wanted to spare his life, but because of his subordinates, his order did not reach them in time. Of course, this was a special case because he wanted to save his friend. But we don’t know of any other cases where he wanted to save people or stop the massacres. And if he had disagreed with them, if he had wanted to stop them, but his men would not listen to him, then he could have resigned his command of the Romanian troops in protest. By not doing so, he became responsible for these atrocities. And also the fact that these massacres took place in and around the territory of his command shows that he is fully responsible for them. How could the leaders of the Romanian militias in northern, southern, and eastern Transylvania more or less protect their men from massacres, but only he couldn’t? This is, of course, a rhetorical question… So we can say that he has no excuse.

That is why it is surprising that of all the other Romanian leaders of 1848-49, he is the one who receives the greatest respect, and celebrations, statues, streets, squares, and institutions are named after him, and commemorative years are dedicated to him with hundreds of celebrations. Why do not celebrate those who were against the confrontations, those who committed fewer crimes, or those who tried to reach a compromise and peace with the Hungarians? Because many Romanian participants in the events of 1848-1849 were in favor of a peaceful agreement with the Hungarians. Nevertheless, he is the most celebrated hero and the demigod. This leads to the question of whether the official Romanian nation and state ideology is defined by hatred of the Hungarians.

On April 20, 1849, during the victorious Spring Campaign, in which the Hungarians drove the Austrian troops out of their country and approached Vienna, the Romanian revolutionary from Wallachia, C. A. Rosetti, wrote the following to another politician, Ion Ghica:

“Ah, the Hungarians, the Hungarians! Tell me, when you hear that name, don’t you want to put a bag of ashes on your head? Doesn’t it make you want to take a gun and start with Eliad and end with you [kill them all and commit suicide]?

Shame and shame a thousand times over! What am I saying? I curse those men, of whom I am the first, who lost the glory of the Romanian nation and brought upon it the suffering and shame of slavery! Ah! If we had been a Romanian government, this glory of freeing the world from slavery would have been ours, not the Hungarians’! And united with the Hungarians, we would certainly have occupied Vienna and proclaimed the Republic, while now we tremble and wait to collect the crumbs of the Hungarian feast!”

Although he does not mention Avram Iancu, he refers to him, among others, and points out that if the Romanians had accepted the promises and gestures of the Hungarians, united with them, they could have defeated the Habsburgs and their allies and together proclaimed freedom and democracy in Europe.

After all this, how can the Romanian leaders, among them Avram Iancu, not be blamed for the deaths of so many Hungarian and Romanian civilians between October 1848 and August 1849? We can ask: why are not, for example, C.A. Rosetti, Ioan Lemeni, and Ioan Dragoș (a martyr who gave his life for the Romanian-Hungarian reconciliation) or others like them, Romanian national heroes, but Avram Iancu?

And now let us ask if he was such a great hero, such a David against Goliath, such a Leonidas against the mighty empire, such a fearless warrior as the Romanian narrative tries to make him out to be. Perhaps that is why he is so revered.

Was Iancu a great military leader, worthy of respect and admiration?

Let’s put aside the massacres in which he and his subalterns were involved and analyze whether he can really be called a hero for his military deeds.

The Romanians present the fight of Avram Iancu against the Hungarian army as an unequal fight of the poorly equipped, heavily outnumbered Romanian peasants against the Hungarian professional army, which ended with the victory of Avram Iancu and the ignominious defeat of the Hungarian soldiers.

But the reality was quite different. From 1848 until May 1849, the troops led by Iancu were defeated by the Hungarian troops in almost every open-field battle. But after the Austrian and Russian troops retreated from Transylvania, he and his troops took refuge in the Western Transylvanian Mountains, which were an excellent terrain for the guerrilla warfare that Iancu and his troops were suited for. These mountains were also home to the Romanian mountain people called Móc, where Iancu’s most loyal troops lived, and therefore they knew every gorge, cave, forest, and hiding place in these mountains.

Thanks to this, it was very difficult for even the strongest and largest armies to successfully attack these mountains. Colonel Farkas Kemény wrote that the number of Avram Iancu’s troops was 70,000 (10,000 riflemen and 60,000 spearmen). Even if Kemény’s claim could be exaggerated, we can count at least 20,000-30,000 men. Many of them did not have firearms but had converted scythes and other agricultural or forestry tools into weapons.

However, many of them also carried firearms provided by the Austrian garrison of Gyulafehérvár or taken from the civilians they attacked and killed. They had no cavalry, and their artillery consisted of cannons made from the pipes of pumping machines used in the mining district (other sources say they made wooden cannons).

Despite the Romanian claims that huge Hungarian armies attacked Iancu, the truth is as follows. Except for the campaign of Farkas Kemény from the beginning of June 1849, the other attacks were made by poorly armed national guards and guerrillas (some of them had only spears), because the professional troops (Honvéds) were used against the Austrian and Russian armies.

The troops led by Imre Hatvani were on the same level as Iancu’s in terms of weapons and military training. Hatvani was not a military officer, but a guerrilla leader who used speeches to convince some civilians to join him and form a militia.

Read more about it here: https://shorturl.at/Nbnnt

Hatvani’s first campaign was conducted with 1109 militiamen on foot, 52 hussars and 3 small caliber cannons (Source: Hermann Róbert. Az abrudbányai tragédia. Budapest 1997, p. 102). He was able to repulse most of the frontal attacks of the thousands of Romanians and suffered defeats mostly during the retreat, caused by ambushes, blocked roads and destroyed bridges on the way back.

The second attack of Hatvani was carried out with 1300 men, with the same results (Source: Hermann Róbert. Az abrudbányai tragédia. Budapest 1997, p. 147). The Romanians, encouraged by these successes, tried to launch attacks from the mountains. One such attack, under the leadership of Avram Iancu himself with 7-8000 men, took place on May 30th against the Hungarian army besieging Gyulafehérvár, but it was repulsed by the Hungarian troops.

Source: https://mek.oszk.hu/09400/09477/html/0021/2205.html

This again shows that when Avram Iancu tried to attack professional troops on open ground, even when these troops were caught in the middle between the besieged fortress and Iancu’s attack, they managed to defeat the latter. As John Paget’s very precise description shows:

“In the open country they [the Romanians] will not stand fire at all, but here [in the mountains] they hide behind every bush & stone & our troops find themselves at once exposed to fire on all sides without being able to seize the enemy”. (Henry Miller Madden: The Diary of John Paget, 1849. The Slavonic and East European Review, Vol. 19, No. 53/54, The Slavonic Year-Book 1939 – 1940, p. 250).

From the summer of 1849, the situation for the Hungarian army became desperate, as the Austro-Russian invasion of Transylvania with more than 50,000 soldiers was imminent, but General Bem had to maintain a blockade of troops around the mountains to prevent the Romanians from attacking the innocent civilian population. So Bem decided to send militarily trained troops against Iancu to crush his threat.

As a result, at the beginning of June, Bem sent Colonel Farkas Kemény with 4000 soldiers (Source: Dragomir, Silviu 1968, Avram Iancu, ediţia a II-a, Bucureşti: Editura Ştiinţifică, p. 209). They also had artillery. Although his guns caused more problems than help to his troops due to the uneven terrain, river crossings and mountain passes, Kemény managed to occupy Abrudbánya again, but they could not force the Romanians to an open battle, and were constantly harassed by their troops, were attacked at night, in the mountain passes, and although they repulsed all the attacks, they began to run out of ammunition (during their retreat they had only 600 cartridges left) and food, as their supply road was cut.

So on June 15, Kemény retreated, beating back every surprise attack and ambush of Iancu’s army. In addition to the terrain, which was unsuitable for open fighting, Kemény blamed the large number (tens of thousands) of Romanian troops for his lack of success, claiming that he needed at least 25,000 troops to force the rebels to lay down their arms.

Source: https://real-j.mtak.hu/15912/1/aetas_1992_001_002.pdf , page 51.

Thus, on the eve of the Russian intervention, the insurgents continued to tie down a significant portion of the Hungarian forces in Transylvania. At the beginning of July, the troops camped around the Ore Mountains and prepared for another attack on Bem’s orders, but it was soon called off because of the Russian invasion of Transylvania.

However, the decision did not reach the Rákóczi Guerrilla Unit (Rákóczi Szabadcsapat), reinforced by other inferior, mostly inexperienced units, led by the history teacher Pál Vasvári, which was surrounded by Romanian rebels at Havasnagyfalu (Mărișel) on July 5 and 6 and was forced to retreat. In the bloody battle, the commander himself was killed and his body was never found.

Read: https://shorturl.at/zaG7k

As the name suggests, Vasvári’s 2000-man force was largely made up of untrained, poorly armed militiamen, volunteers, reserve troops who had never fought, and recruits, while its leader also had no military experience, being one of the young intellectuals of the March Youth who carried out the March 15 Revolution along with the poet Sándor Petőfi and the novelist Mór Jókai.

Colonel Farkas Kemény was indeed a talented Hungarian officer who fought as a subordinate of Lieutenant General József Bem, but he was not a great military leader like Bem or Generals Artúr Görgei, János Damjanich, György Klapka, Antal Vetter, Károly Vécsey, etc.. He never led troops alone against Austrian or Russian troops and could prove his value as a military leader who could defeat enemy troops alone.

Read the source: https://shortlurl.com/DZaB

Before his campaign in the mountains from June 1849, he only distinguished himself in some victories against the Romanian troops, like on March 23, 1849 at Nagyenyed and on March 25, 1849 at Diód. But he showed his bravery as a good officer under Bem in many battles like Csucsa or Piski. But when he had to lead a troop alone and make decisions for himself, he was not the best choice. So we can conclude that he was a good subaltern, but not a good military leader. Nevertheless, he did not suffer a tactical defeat at the hands of Avram Iancu.

Thus, except for Kemény’s 4000 soldiers, all of Avram Iancu’s battles were fought against untrained militias and volunteers of about 1000-1500, led by civilians. The Romanian troops facing these Hungarian militias and Kemény’s troops always had a huge numerical superiority, on advantageous mountainous terrain.

When they attacked on open ground, despite their superior numbers, they lost almost every time. For example, on June 9, in the battle of Nagyhalmágy, a Romanian force of about 4000 men was defeated by the 1170 men and 14 cannons led by Major István Csanády.

To call Avram Iancu a Robin Hood who fought alone against the oppressive empire is again wrong, because the Romanians allied themselves with the Habsburg Empire.

In reality, the Hungarians can be called Robin Hood or David against Goliath because they fought against two empires (the Habsburgs and Russia) as well as their Serbian, Croatian, Slovakian and Romanian allies.

During the Summer Campaign of 1849, the Hungarians had about 152,440 soldiers and 472 cannons, and together with the 20,000 militiamen and guerrillas fighting beside them, they did not exceed 172,440.

Source:https://shorturl.at/QSgqr

The Austrian-Russian coalition had around 357,475 professional soldiers and 1354 cannons.

Source: https://shorturl.at/iYgP5

In addition, there were 900 Slovak militias (Source: Hermann Róbert: 1848-1849 – A szabadságharc hadtörténete. Korona Kiadó Kft. Budapest 2001, p. 39) who fought with them. We are not counting the 58,687 Russian troops and 48 cannons held in reserve in Galicia, which had to intervene in Hungary if necessary.

Source: https://shorturl.at/ryJL7

Therefore, the Hungarian army with 172,440 men and 472 cannons fought against a coalition of two empires and the Romanians of Avarm Iancu with a total of 428,375 men and 1354 cannons. Not to mention the superiority in arms, ammunition and quality of weapons that were also on the side of the Austro-Russian armies. So who was the Leonidas or the Robin Hood?

Was Avram Iancu a hero in battle? John Paget says about him: “He [Miklós Bethlen] says that the officers never come under fire, and Jank [Avram Iancu] himself (who is always drunk) has never been in battle. Jank keeps the greatest discipline among his men & often has them shot for disobedience”.

(Henry Miller Madden: The Diary of John Paget, 1849. The Slavonic and East European Review, Vol. 19, No. 53/54, The Slavonic Year-Book 1939 – 1940, pp. 250)

As we can see, he was not the type of man who would go into battle and try to encourage his men by his example, and his subordinates also avoided appearing among their men to personally lead them against the enemy or to turn the tide of battle by encouraging their wavering men on the battlefield.

In contrast, the Hungarian generals and officers often appeared among their men and led them into battle. General József Bem, for example, was often among his soldiers in the heat of battle and suffered countless wounds.

For example, in the battle of Szászváros on February 5, 1849, the Austrian soldiers captured the Hungarian guns, and Bem rode up and hit a soldier in the face with his whip, saying: “Leave my guns alone!” The soldier fired at him and shot off the thumb of his right hand. Or the greatest commander of the Hungarians, Artúr Görgei, who in the battle of Komárom on July 2, 1849, personally led the charge of the Hussars against the overwhelming Austrian and Russian troops, and at one moment was wounded on the head by a splinter of an enemy projectile fired from a rifle, which opened his skull and almost killed him.

Regarding Iancu, who was drunk all the time, he did not distinguish himself by his bravery. He sent his troops into the attack, which suffered heavy losses from the Hungarian guns, bayonets and rifles, but he never went among them to encourage them or lead them.

As I see the reality, Avram Iancu does not deserve such high esteem and celebration because his military deeds were not exceptional and almost all his successes were achieved against poor quality guerrillas led by inexperienced men. The only success that can be taken into account is that of forcing Kemény Farkas’s troops to retreat, but even this was achieved not by confrontation, but by guerrilla-type attacks, ambushes, and by cutting off his supply routes.

At a time when warfare was characterized by battle lines, the confrontation of large compact units (the most notorious examples are the huge casualties of the American Civil War caused by the volleys of troops facing each other), Avram Iancu used guerrilla warfare, characterized by hit-and-run tactics, ambushes, night raids, cutting the enemy’s supply lines and attacking the undefended civilian population, with which he tried to create fear and terror, forcing the enemy to send troops to defend them, thus weakening their combat-ready army.

While against Kemény’s soldiers this kind of warfare is somehow explainable (even though the Romanians greatly outnumbered them), against the untrained, much less numerous militias led by Hatvani and Vasvári it cannot be explained. Therefore, it is hard to explain why he is celebrated so much in Romania. Is it because he killed so many Hungarian civilians?

His later years and death

After the Hungarian Revolution was defeated with the help of Russia and the Romanian troops were disarmed by order of the Austrian commander-in-chief, Field Marshal Julius von Haynau, Iancu spent several months in Vienna in 1849.

His expectations of the Emperor’s reward for the help the Transylvanian Romanians had given to the Austrian army against the Hungarians were far greater than the Emperor’s court appreciated. At the same time, the fact that at the end of the War of Independence a truce had been agreed between Iancu and Kossuth was not a good point for him. Iancu’s trip to Vienna was unsuccessful, and Vienna first delayed and then openly refused to meet Romanian national demands.

On another occasion, the Emperor wanted to decorate him for having fought against the Hungarians, but Avram Iancu refused to accept it.

The Emperor Franz Joseph visited Transylvania in 1852. Although the route determined by the Emperor’s advisors avoided the Western Transylvanian Mountains, the site of the Romanian Resistance, the Emperor changed his route to visit the region at Iancu’s insistence. During Franz Joseph’s visit to Transylvania, Iancu himself organized the reception of the Emperor in all the villages of Móc, and his excellent organizational skills and influence on the people ensured that Franz Joseph was greeted with a true procession of celebrations worthy of an emperor.

Nevertheless, for most of the visit Avram Iancu avoided meeting the Emperor when he had the opportunity, and he finally reported for an audience at Topánfala late in the evening, after the Emperor had gone to bed. When he was told to return in the morning, he tried to persuade the head of the cabinet to wake up the emperor, but eventually it took the intervention of the imperial guards to remove him when he became out of control and violent. On August 17, 1852, he was arrested and taken to Gyulafehérvár under gendarmerie escort. During the few days of his imprisonment he was severely beaten.

All this sheds a very clear light on the collapsing mental health of the increasingly erratic Avram Iancu. He began to drink heavily, which contributed to his deteriorating mental health.

Slowly, he began to fall out with all those he fought with and began to distance himself from them.

He should have known that the Serbs, who had helped the imperial forces, had been granted their long-sought self-government, known as Vojvodina in southern Hungary, and that the demands of the Croats had also been largely met. The Romanians’ demands, however, had not been met.

Iancu may well have felt that the reason for this was precisely the way he had led the resistance, that he had failed to make any substantial contribution to stopping and defeating the Hungarians, and that the large-scale massacres he had caused and failed to prevent had brought the Habsburg Empire into international disrepute.

All this probably made him feel guilty, and perhaps the massacres of Hungarian civilians made him feel increasingly remorseful. He may have regretted that he had ignored the Hungarian promises of the summer and fall of 1848 and allied himself with the treacherous Empire, causing the deaths of thousands of people.

He could not help his people gain more rights, but he was the cause of tens of thousands of deaths. All this gradually drove him into a state of mental imbalance and insanity. And in 1867, his former allies and enemies made an agreement and the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy was founded, which gave back to Hungary all the rights won in the Revolution of the Spring of 1848.

This was the ultimate betrayal of the Emperor, which may have been the final blow to Avram Iancu’s mental health. In this regard, we can say that Avram Iancu was indeed a tragic hero, but this cannot wash away his guilt for the loss of so many thousands of innocent lives.

In his last years, the leader of the Móc, forgotten by everyone, poor, in rags, and with a distracted mind, wandered through the mountains playing his flute.

Even his Romanian comrades-in-arms, his loyal officers, forgot him and left him alone. In the last decade of his life, “Uncle Janku” was fed by Hungarian families who took pity on him, and he died in Kőrösbánya on September 10, 1872. Now, Avram Iancu, who was forgotten by his people in his last years, was buried with great processions by a large number of Romanians.

He was buried in Cebe (Țebea) under the oak tree of Horea, the leader of another Romanian uprising responsible for the deaths of some 5,000 Hungarian civilians.

One last question we have to ask: why was he and his other comrades not prosecuted and convicted for the crimes they committed against the Hungarians in 1848-49? As we have seen above, after the suppression of the Hungarian revolution, the Habsburgs took into account only the Romanian and German victims of the civil war. They knew that they were also guilty of the massacres committed by the Romanians, and in many cases they were the ones who incited them to commit these acts.

After the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, Hungary regained its autonomy, but not its independence, and for this reason it was out of the question to bring Avram Iancu, Axente Sever, Balint, Dobra, etc. before the tribunal, because the trial would have revealed the guilt of the Austrian army, authorities and eventually even the Emperor. Thus, Avram Iancu and his comrades could live and die without being prosecuted for their crimes. For example, Axente Sever, who led the Romanian troops that massacred about 1000 civilians in Nagyenyed, died in his bed in 1906.

Sources and other references:

https://epa.oszk.hu/00400/00458/00423/pdf/Korunk_EPA00458_1972_09_1333-1340.pdf https://magyarnemzet.hu/velemeny/2022/05/avram-iancu-a-roman-nemzeti-hos https://foter.ro/cikk/20151030_avram_iancunak_magyar_szeretoje_volt/ https://eres.blog.hu/2011/06/10/avram_iancu_hos_vagy_gyilkos_1_b

Also: Hermann Róbert: Az abrudbányai tragédia, 1849. Heraldika, 1999

Gracza György: Az 1848-49 iki magyar szabadságharcz története I-V. Históriaantik Könyvesház, 2011

Szilágyi Farkas: Alsófehér Vármegye Monográfiája. III. kötet. Nagyenyed 1898

Egyed Ákos – Erdély 1848–1849. Pallas-Akadémia Könyvkiadó, 2010 Csíkszereda

Author of the article: Szilágyi Szilárd

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts:

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital, they are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! and donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://shorturl.at/qrQR5

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://shorturl.a