The first part of the War – the Prelude

The Venetian-Hungarian War, known in Italian as the Chioggia War (Guerra di Chioggia), lasted from 1372 to 1381. It broke out during the reign of King Lajos (Louis) I (the Great) and was the third war between the Kingdom of Hungary and the Maritime Republic during his reign, but also, in a broader sense, the war between the Republic of Genoa and Venice. The Ottomans supported the Venetians in the Hungarian-Venetian war, that is why we have to look at it. It was one of the first clashes between the Ottomans and the Hungarians.

The Hungarian-Venetian War was actually about gaining sovereignty over Dalmatia. Hungary has been interested in the sea ever since it acquired Croatia. King Kálmán the “Bookish” took steps to this end, and with him began the wars with Venice, which lasted until the 15th century and were fought with varying degrees of success. The two countries had been fighting for hegemony over the territory since the Árpád era, but only now was the outcome decided in favor of the Hungarians. You can read more about the life of King Nagy Lajos on my page: https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/essays/king-lajos-i-the-great-r-1342-1382/

In these battles, the disputed Dalmatian cities preferred to see the Hungarian king at their head. The cities, and especially the Republic of Raguza, were a serious rival to Venice on the Adriatic, and the Doges were determined to eliminate them so that nothing would stand in their way. The Hungarians did not interfere in the affairs of the cities as much as the Venetians or the Byzantines, which is why the Dalmatian cities were Hungarian-oriented. Under Hungarian rule, the archbishopric of Spalato remained independent, and Trau, Spalato, Zara, and Raguza also retained their independence and were granted privileges by the kings.

King Lajos immediately launched a war against Venice in 1346 but was heavily defeated in the first phase, forcing him to make a truce that lasted until 1355. This time he had to turn his attention to Naples, from where he also returned without success.

In 1355 he defeated Serbia and then turned his attention back to Venice. The reason, of course, was Padua, whose lord, Prince Francesco da Carrara, wanted to preserve his city’s independence from the Doge. While Padua attacked the Venetians in Venetian territory, the Hungarians attacked them in Dalmatia, only to be stopped at Treviso. In 1357, however, the Hungarian troops defeated the Venetians there and the city-state was forced to make peace in 1358.

The second part of the War

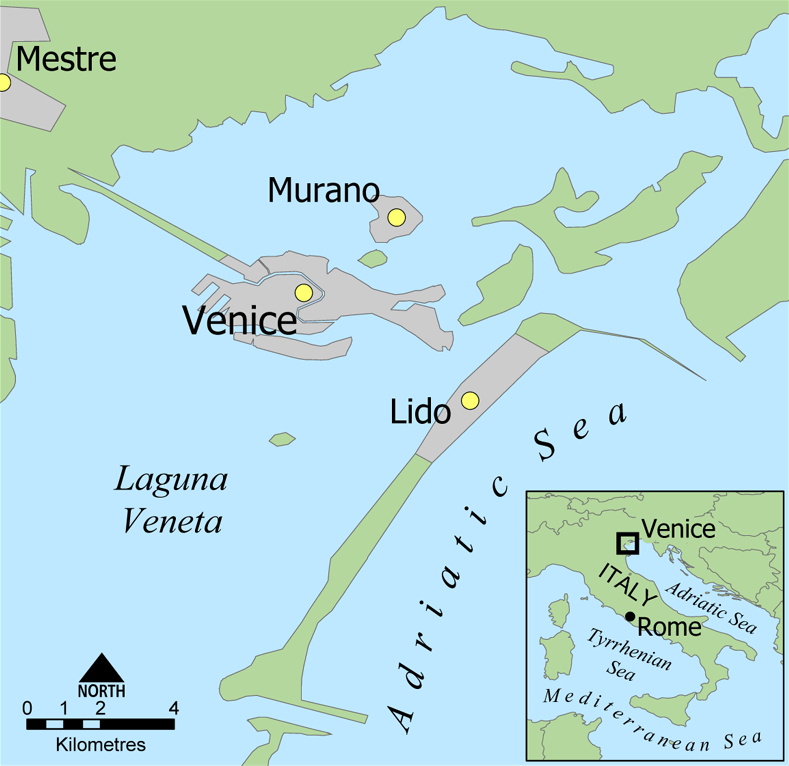

King Lajos I (Louis) got into a conflict with Venice in 1372 and unfortunately, the Venetians were allied with the Turks. Venice had participated in the dismemberment of the Byzantine Empire in 1204 and had gradually taken over land on the Adriatic, getting into conflict with Hungary, while on the Italian mainland, its land acquisition had created a rivalry with the nearby largest city, Padua.

At the same time, Venice had the support of John V Palaiologos, Byzantine Emperor, and hired several thousand Ottoman soldiers. When Venice threatened Padua in 1372, Hungary and the Germans of present-day Austria allied with Genoa to defend Padua. We know that King Lajos had previously used Paduan crossbowmen in his army. King Lajos sent 4,000 Hungarian and 1,000 German (Austrian) cavalrymen to Padua in 1372.

They were led by Lackfi István, Himfi Benedek, Czudar György, and the archbishop of Esztergom, Telegdi Tamás. They arrived in Padua in May 1373 and joined Da Carrara’s army. Together they defeated the Venetians in an open battle at Piove Sacco.

After that, the Hungarian soldiers (including the Kuman warriors) began to behave like undisciplined mercenaries and demanded more money from Padua, so King Lajos had to write a letter and warn his generals that there was no need to get more money as the men had been paid for three months. He added that they were only allowed to get money from Da Carrara as a loan.

King Lajos declared a full-scale war on Venice when he learned that the Venetians had brought in 5,000 Ottoman warriors to help the Italians besiege Treviso which was defended by Paduan and Hungarian troops. The Turkish reinforcements arrived on July 1st and together with the Venetians they defeated the forces of General Lackfi. The Hungarians had suffered great losses in Treviso, they had many casualties and suffered damages worth 300,000 florins, they also lost 30,000 (?!) horses.

This war partly motivated King Lajos to start his third campaign against the Turks in Wallachia in 1374. During the armistice, King Lajos was preoccupied with his children’s engagements and the Turkish campaign in Wallachia, but he was also consciously preparing to fight back against Venice.

As for Venice, after the king had ransomed the captured Hungarian soldiers, war broke out again.

The third part of the War

In 1378, King Lajos allied with the Republic of Genoa. The two Italian republics had long been at odds over the Levant, and Genoa seized another opportunity to defeat its rival. Another reason was Cyprus, over which Genoa also wanted to gain sovereignty, and this made the situation rather worse. The Cypriot navy was also involved in the war against the Hungarians and the Genoese.

The alliance was soon joined by the Patriarch Marquardo di Randeck of Aquileia and Verona, and the united Hungarian-Genoese-Paduan troops led by Himfi and Horváti János repelled the enemy. In this campaign, they did not engage in open combat, which was too risky, but tried to weaken each other through ambushes, sieges, and raids. Since King Lajos relied on his light cavalry as well as on his heavy cavalry, the horse archer Kuman warriors of Hungary could likely have been brought to this campaign as well.

A small note: Venice was originally built on water because of the fear of Attila the Hun’s attacks. One can imagine that the inhabitants associated the Hungarians with the fearsome warriors of the Huns. At that time it was common in Europe that the Hungarians were considered to be the late sons of King Attila. It is easy to imagine the devastation caused by the Kuman cavalrymen, who must have resembled either Attila’s Huns or the pre-Christianized Hungarians of the 9th and 10th centuries.

In June the Allies were already in front of Mestre, directly threatening Venice, and on June 26 a Hungarian army of 5,000 men marched into Padua. These troops, together with Friulian soldiers, besieged San Lorenzo, which they took after a long battle. The Venetians tried to take Trau, also without success.

Despite Vittorio Pisani’s victory over the Genoese near Istria the previous month and the ambush of Luciano Doria’s troops on May 7, 1379, the Genoese fleet trapped the Venetians in the port of Pola, then captured the strategic Chioggia at the entrance to the Gulf of Venice and defeated the Duke of Milan, Bernabò Visconti at Bisagno.

In desperation, Venice sent envoys to Hungary to negotiate a possible peace. The king negotiated with them only through two bishops and Kis Károly (Charles of Durazzo, later king of Hungary between 1382 and 1386), so no decision was reached.

A side-note about Charles of Durazzo: Following the death of his father, Prince Louis of Durazzo Anjou, Charles of Durazzo entered the Hungarian royal court as a young prince, where he became a talented commander under King Lajos the Great of Hungary. It was the reason why he acted as a diplomat for the king.

After a series of military defeats, Venice offered to negotiate and even agreed to swear an oath of allegiance to the Hungarian king. However, under pressure from Padua and Genoa, King Lajos demanded very harsh peace terms: an annual tax of 100,000 gold pieces and the surrender of Trieste, which Doge Andrea Contarini naturally refused to accept.

During the negotiations, the fleet was restored and the blockade of Genoa was broken. While the Genoese were fighting in the Adriatic and Cyprus, a revolt broke out in Genoa, which was in crisis on both fronts.

In addition, the Hungarians almost succeeded in turning Mantua against them, as Hungarian troops marching through the countryside plundered the duchy. Ludovico (Louis) II of Gonzaga was furious with the Hungarian king for not ordering the Hungarian leader, Maróti János, to do his bidding. In response, King Lajos vowed to do so severely.

On June 27, 1381, the Venetian fleet carried out another large-scale operation off the Dalmatian coast.

After the War

From 1380, negotiations began on a new basis, and on August 8, 1381, the Peace of Turin was signed with the Venetians. This treaty preserved the independence of Padua and established Hungarian rule in Dalmatia, which lasted until the 16th century and was only threatened by the Turks, who conquered Bosnia in the 15th century. The Ottoman Empire gained control of parts of the province in the war of 1521-26, and the rest was conquered by the Croats over the next nearly half-century.

For Genoa, the war was also a major financial and military strain, and it was effectively defeated, while Venice continued to grow stronger, so that from the 15th century onwards it no longer faced serious competition from Genoa. However, the war took a heavy toll on Venice’s economy.

Despite the defeat, Venice’s power was not diminished and it remained a dominant player in the region until 1669. After this battle, however, its naval power was no longer to be feared by Genoa or Hungary, but by the very people it had called upon to help it besiege Treviso in 1373 – the Ottoman Turks.

The Turks had already attacked the ships of Genoa and Venice in the Greek seas in the 14th century, but after conquering more of Bosnia and Albania, the Turks were now able to establish ports in the Adriatic, from where they looked towards Naples, the Papal States and Venice.

In a strange irony of fate, Venice found itself facing a new and dangerous enemy that it had called upon to help it against the Hungarians, namely the Ottoman Empire.

Let me note that when the Turks established a bridgehead in Italy in the 15th century, it was the Hungarian general Magyar Balázs who broke their power by recapturing Otranto in 1481, thus saving Italy from being overrun.

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts:

Please, feel free to support me with a coffee here: You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital, they are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook: https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!