Perényi Péter (1502– 1548), and his „third way”

Perényi Péter was a powerful Hungarian aristocrat, the guardian of the Hungarian Holy Crown, the Voivode of Transylvania. His family had played an important role before the Battle of Mohács (1526), where he fought bravely. After the death of King Louis II, the era of Dual Kingship began in Hungary, which led to the destruction of the country. We know that it was King Szapolyai who was first crowned, then he was attacked by the Habsburg Ferdinand who usurped the throne and was also crowned.

One might think that either King Habsburg Ferdinand I or King Szapolyai János was the answer to the survival of the Kingdom of Hungary during their simultaneous reign over the Ottoman-threatened country. However, Hungarians are still divided as to which of the two monarchs was right. But the question suddenly arises: was there a third candidate who might have been better than them?

The “third way” would have been Perényi Péter or his son Ferenc as king of Hungary; but we know that it was among Perényi’s plans to establish a system in Hungary similar to that of Venice, where he would have been the elected leader of the “noble community”, like the Doge of Venice. Could it really have happened? Was Perényi far from achieving his goal? What if he had been much better than Szapolyai or Ferdinand? That remains to be seen forever, but let us get to know him a little better.

Péter was the son of Palatine Perényi Imre and the brother of Bishop Perényi Ferenc, who died with a sword in his hand in Mohács. The Perényi family was descended from a German family that settled in Hungary in the valley of the Hernád River in the 13th century. Later the family held high positions in the Kingdom of Hungary. (Note: I am intentionally using the Oriental name order for Hungarians.)

To understand the power and influence of the Perényi family, let’s go back a few years before Mohács. In 1516, three years before the death of Perényi Imre, at the Rákosmező Diet on April 24, the barons and estates of the country approved the 10-year-old Louis as their king with full authority and they appointed a council around him. Perényi Imre was a member of this council: in fact, they led the country (towards Mohács). A few months later, after the Board had started its work, Count George Brandenburg (the nephew of the late King Ulászló and one of the tutors of the young Louis II) agreed with the Palatine Perényi Imre and Voivode Szapolyai to divide the huge Hunyadi lands between them.

Old Perényi Imre became the godfather of a Spanish Jew named Fortunatus or Salamon ben Efraim, who took over the financial affairs of the kingdom with Perényi’s support. Later, Fortunatus was accused of fraud by Szapolyai and they also blamed him for the loss of Nándorfehérvár (Belgrade) in 1521.

The Perényi family owned important castles such as Terebes, Füzér, Csorbakő, and Újvár, not to mention Dédes Castle, which I have just presented on my page:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/ottoman-occupied-lands/dedes/

The family was the hereditary Chief Comes of Abaúj County, and Perényi Imre had participated in the signing of the Habsburg-Jagellonian Treaty and as a result, received the rank of Prince of the Holy Roman Empire. They acquired other castles in the southern part of Hungary (Valpó Castle and Siklós Castle in Baranya County), Debrő Castle in Heves County, and Ónod Castle in Borsod County.

Perényi Péter inherited all these castles and also became the Chief Captain of the Castle of Temesvár (Timisoara). He was a member of the only knightly order established in Hungary, the Societas Draconistrarum (Sárkányos Lovagrend), and acted as the guardian of the Holy Crown of Hungary.

After Mohács, 1526…

While Bishop Perényi Ferenc died with a sword in his hand, Péter fled from the Turks and took the Holy Crown to the fortified castle of Trencsén in the north of Hungary. After that, he became a follower of King Szapolyai and gave him the Holy Crown for the coronation, but they did not like each other. Nevertheless, he was appointed Voivode of Transylvania and fought the invading troops of Cserni Jován’s Serbs until 1527 and defeated them at Szeged. He was joined in this campaign by the peasant soldiers of the late Dózsa György. It is interesting to note that it was Szapolyai who had brutally suppressed their uprising in 1514.

The Holy Crown was kept in the castle of Füzér instead of Visegrád, from where Perényi took it to Archduke Ferdinand on November 3, 1527, and allowed him to be crowned with it. In exchange, he received the castle of Sárospatak and the money of the Eger bishopric, which was compensation for his lost property in the hands of Szapolyai. After the coronation, he took the crown to the castle of Siklós and in 1529 to the castle of Sárospatak.

He had only a few hundred soldiers to guard the crown on the way, and unfortunately, he met the unit of King Szapolyai’s troops led by the chief commander (and bishop) Szerecsen János at Kajdács. Perényi’s troops were defeated and all were captured and King Szapolyai gave Perényi to Sultan Suleiman in 1529. Suleiman heard that the crown was guarded in Slavonia, in the castle of Sopron (in the castle of Bánfi János) and he wanted to “see” it. He sent 300 Sipahi horsemen and they brought the crown to him. As for Perényi Péter, he was in the captivity of Bishop Szerecsen János of Pécs.

To Szapolyai’s surprise, the Sultan found Perényi more valuable alive and released him. Perényi had to serve King Szapolyai again in exchange for his life. He was the one who escorted Queen Isabella to his new (or old?) king. As for the Holy Crown of the Hungarians, Sultan Suleiman understood that it had to be returned to Szapolyai. Without the crown, no one would have followed Szapolyai, and after the unsuccessful siege of Vienna in 1529, Suleiman did not have enough power to overrun Eastern Hungary. He had to pacify Szapolyai, so the crown was returned to him.

King Szapolyai could achieve the temporary independence of Eastern Hungary, there were no Turkish garrisons in his country. However, the Dual Kingship had a very harmful effect on the kingdom, the nobles changed sides quite often, depending on who they considered a better protector against the Ottoman threat. Perényi Péter was a leader of the Hungarian nobles’ party who disliked both Ferdinand and Szapolyai. He and some important Hungarian barons went to Venice in the summer of 1531 to negotiate the seizure of power in Hungary. At that time, King Szapolyai was still childless, and the Doge’s bastard son, Lodovico Gritti, was the Sultan’s governor of Hungary, authorized to give instructions to Szapolyai on behalf of Suleiman.

Lodovico, obviously a thorn in Szapolyai’s side, wanted to be named the new king of Hungary. Perényi wanted to undermine his efforts with Andrea Gritti, the Doge of Venice. Perényi arrived in Venice with a rather impressive force of 600 hussars and tried to persuade the Doge to support his claims to the throne if Szapolyai happened to leave no heir.

At the same time, Perényi’s envoys, Zrínyi Miklós (Nikola Subic Zrinski) and Bika Imre, tried to convince the Sultan in Istanbul that Gritti and Szapolyai were not a good choice. However, it was in vain to send a large golden chalice and a sapphire ring worth 12,000 ducats to Grand Vizier Ibrahim, as Lodovico Gritti proved to have greater influence in Istanbul. Soon Suleiman was informed of the plot and had Perényi arrested when he visited the Sultan in 1532: they arrived as guests, armed with Suleiman’s document for their protection, but his men were slaughtered on the spot.

Now it was Suleiman who gave Perényi to King Szapolyai János and Perényi had to swear fealty to him for the third time. But this time he had to pay an enormous sum and his 8-year-old son Ferenc was taken hostage to Istanbul. Suleiman had big plans for the little boy.

Soon Lodovico Gritti lost his best supporter, Vizier Ibrahim, and his position in Transylvania was weakened, especially after he had brutally executed Bishop Czibek Imre. Perényi’s main motivation at this time was to get his eldest son, Ferenc, back by any means necessary. Meanwhile, Gritti was beheaded by the Hungarian nobles of Transylvania in 1534. Immediately after this, Perényi asked the Voivode of Moldavia to give him Gritti’s two sons in exchange for his son, but the Voivode of Moldavia wrote him that unfortunately, he had already executed them.

Perényi’s chances of getting his son back diminished when the Turks were informed that the negotiations between Habsburg Ferdinand and Szapolyai were taking place at Perényi’s castle in Sárospatak. Finally, Ferdinand and Szapolyai made peace and this angered Suleiman. Nevertheless, Perényi did not think that Ferdinand was strong enough to defend Hungary, so he and his party wrote a letter to Emperor Charles V, Ferdinand’s brother, suggesting that Ferdinand be removed from the Hungarian throne if he was unable to fight off the Turks.

Szapolyai died in 1540, but against all expectations, he left behind a male child born at the same time, named János Zsigmond. Buda Castle fell to the Turks in 1541, and since Perényi was no longer Szapolyai’s sworn man, we find him again on the side of King Ferdinand, who quickly appointed him his chancellor and promised to get his child back. Let us not forget that Ferdinand could not have been crowned in 1527 without Perényi.

King Ferdinand sent Joachim of Brandenburg with his small and poorly equipped army to recapture Buda in the summer of 1542. Suleiman sent his reinforcements against them (in his army was Perényi’s son Ferenc, a 20-year-old boy at that time). The leader of the Hungarian army was Perényi himself with 15,000 men and they could take Pest, but the campaign ended in disaster. Ferdinand suspected Perényi of treason and had him arrested in October.

Suleiman had offered to release Majláth István, Török Bálint, and Perényi Ferenc in exchange for the support of the Hungarian lords, we know that for sure. Perényi Péter may have thought that he would be a better leader of Hungary under the Ottoman Empire than Szapolyai’s baby son, knowing that the Turks were not strong enough to colonize Eastern Hungary as they had done with the Balkans. He could have enjoyed more independence in governing Hungary than under the rule of Ferdinand, whose strength proved insufficient to defend the country anyway.

However, Perényi Péter was released from his captivity only after paying 40,000 ducats, six years later, just a few weeks before his death. In prison he wrote religious works, he was a friend of Melanchthon and a supporter of Protestantism. He left behind two daughters and two sons. Without Perényi, Török, Bátori, and noblemen like Thurzó, Szapolyai, and Martinuzzi, the “White Monk”, it is almost impossible to understand this exciting and important period of Hungarian history.

Perényi Péter was buried in the church of Terebes, but later some fanatic Pauline monks dumped his remains, claiming that the lightning had struck the church tower because of the remains of this heretic lord. The story of his life helps us a lot to understand the Dual Kingship of Hungary and we can play with the idea of what would have happened if…

But the story of Perényi is far from its end.

Ferenc, the kidnapped son of Lord Perényi

Ferenc, the Sultan’s hostage

We know that the 8-year-old Ferenc was captured by Sultan Suleiman in 1532. Suleiman lost his faith in Perényi Péter because Lodovico Gritti had revealed Perényi’s plots against him. Gritti, the governor of Hungary on behalf of the Sultan, could have received this information from his father, Andreas Gritti, the Doge of Venice. Remember, Perényi negotiated with the Doge and even made a show of visiting him in Venice with 600 hussars.

Suleiman was made to believe that Perényi had allied himself with King Habsburg Ferdinand and that they were planning to attack the Sultan’s army, which was marching towards Vienna, from the rear using Perényi’s castles at Siklós and Valpó. So Gritti took the boy first to Nándorfehérvár (Belgrade) and then, in April 1533, to the Sultan in Istanbul. According to the unpublished work of Sztárai Mihály (1500-1575): “The Story of Perényi Ferenc’s Escape from Captivity” (1543), he was given a noble upbringing as befits a Muslim nobleman, and he was circumcised as a Muslim. He pretended to have forgotten the Hungarian language, but he never did.

It is said that before sending his army to relieve the siege of Buda in 1542, Suleiman summoned him and tested his loyalty by asking him a few questions. We know that his father, Perényi Péter, did his best to free him, but Ferenc pretended to hate him. The Sultan wanted to make Ferenc the lord of Hungary, maybe even its king. So the boy was given a small Ottoman unit and disguised as a young aristocrat, he was put in charge of them in the army that went to Buda. However, instructions were given to keep an eye on him in secret.

We also know that the Sultan had offered to release Majláth István (later he was the Turks’ candidate to lead Transylvania as a prince) and also Török Bálint. There must have been some reason for these plans, because later, in 1543, the marching Ottoman army avoided and took care not to destroy Török Bálint’s lands and properties. According to hearsay, Suleiman would have returned all the occupied Hungarian lands to these nobles if they had sworn allegiance to him.

To illustrate Perényi’s wealth, his annual income was 100,000 ducats, which was less than the tax Transylvania paid to the Ottoman Empire some 50 years later. In the 1520s, King Lous II had only five times as much income. Perényi was the richest lord of Hungary in the 1530s.

We also know that Perényi Péter was in charge of the Hungarian auxiliary troops of General Joachim Brandenburg, leading 15,000 Hungarians who had taken the city of Pest opposite Buda in 1542. Perhaps the Sultan thought that Perényi Péter would not dare to attack them if Perényi Ferenc was in the Turkish army.

You can read more about the fortified town of Pest here:

The miraculous escape of the boy

However, Perényi Ferenc crossed Suleiman’s plans by running away from the Ottoman army when it was close to the Croatian-Hungarian lands. It was his tutor Sztárai Mihály who wrote down his adventures. As for Sztárai, he fought in the battle of Mohács, then became a Reformed pastor who founded 120 Reformed congregations in the South Trans-Danubian region during the dangerous years of Ottoman expansion. He wrote about how young Ferenc, helped by some Croatians, escaped through hostile lands and was reunited with his mother.

However, his brother Gábor doubted his identity and did not let him meet his father. As for Perényi Gábor, we know that he later had his wife poisoned out of jealousy, and there are stories that he either poisoned Ferenc or drowned him in the Bodrog River just to avoid dividing the family property. Perényi Gábor also kept his mother in deep poverty because she had helped Ferenc to regain some of his father’s inheritance.

We know that Ferenc was still alive in 1546 because he told stories about the Sultan’s Persian campaign of 1535 to a Hungarian singer and musician named Tinódi Lantos Sebestyén (1510-1556).

We know nothing about Ferenc except the brilliant adventures written about him by Sztárai Mihály. His tragic life belongs to the group of questions that begin with “what would have happened if…”.

Nevertheless, I have a feeling that Ferenc could have been a better ruler than the baby János Zsigmond, who became the ruler of Eastern Hungary after 1541.

The end of the Perényi-story

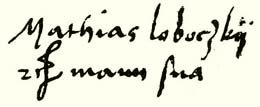

I am going to translate for you the letter written by a Hungarian nobleman, Loboczki Mátyás, to King Ferdinand I of Habsburg on January 01, 1539. It contains some details about the history of Lord Perényi Péter and his son, as well as some interesting information about why the Ottomans did not like to take Hungarian boys to turn them into janissaries. Loboczki was a diplomat of the time, later he became a faithful man to Queen Isabella, the widow of King Szapolyai János. Loboczki’s letter to Ferdinand of Habsburg reads as follows:

“I wanted to write to Your Majesty about what I had heard because it was not only from empty hearsay but from real sources. Let Your Majesty be informed that the Sultan of the Turks (Suleiman), on his return from his campaign in Moldavia, crossed the Danube and summoned those Sanjak Beys who live along the Hungarian Borderland, called two pashas and addressed them with this question:

-You who live on the Hungarian Borderland, you have met the Hungarian lords and you know their reputation. Tell me, do you know any of them who are not traitors?

It was Pasha Aias (?) who answered him with a smile:

– I do not know anyone except Lord Perényi Péter.

The Sultan replied by saying:

– Since the creation of the world, there has never been a greater traitor than Perényi Péter. He betrayed me twice, then he betrayed King János (Szapolyai), King Ferdinand of Habsburg, and his son, his kinsman, whom I have in my hand. I had taken Perényi’s son Péter into my hand because I knew that King János lacked an heir and I wanted to make either Péter or his son the king of Hungary after the death of King János. But now I see that the blood of this traitor is not fit for kingship. – said the Sultan.

The Sanjak Bey of Szendrő (Smedorevo) said:

– My Sultan, you should never believe that a Hungarian could ever be born into this world who would not be a traitor. The Turks have already learned the serious treachery of the Hungarians by paying a high price for it. Such treachery as we have never seen in any nation of mankind. Behold, even those Hungarian children whom we had captured by chance dared to betray their masters. No matter how well we treated them, and no matter what we had wasted on them. Many of their lords were killed in their sleep, so no matter how young our Hungarian captives may be, we never trust them. – This was said by the Bey of Szendrő, but others made similar statements about the Hungarians.

When the Sultan heard all this, he raised his hand and swore an oath that he would go to Hungary with his whole army and either die there with all his men or wipe out the clans of the Hungarians from the surface of Hungary.

To carry out this plan, the Sultan sent his Wallachians, which we call “posts”, to the Crimean Tatar Khans who were rivals among themselves, to make peace between them and prepare them to march against Hungary by the next summer. (…) The Turkish Sultan took an oath and decided to settle the Crimean Tatar nation on the fields of Hungary around the Tisza River and to uproot and destroy the Hungarian nation.”

Sources: Niki GAMM, Stanford Shaw, and Szerecz Miklós

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

If you like my writings, please feel free to support me with a coffee here:

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital, they are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X

or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon:

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/