Let me share with you a guest post from a Romanian author, Horațiu C. Damian about the history of the Máramaros (Maramureș) region. Máramaros is essentially a valley region, bordered by the northern mountains of the inner ranges of the Eastern Carpathians.

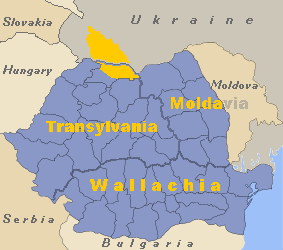

Máramaros (in Romanian Maramureș, in Ukrainian Мармарощина, in Ruthenian Мараморош, in Yiddish מאַרמאַראָש) is a historical region in present-day Ukraine and Romania. It appears in old sources as Máramarosország. Its Ukrainian territory is part of Subcarpathia (Kárpátalja) and its Romanian territory is part of Partium. Geographically, it is located in the north-eastern Carpathians, and is made up of the following geographical areas:

Rahói-hegység (Ukrainian: Рахівський масив), Máramarosi havasok (Ukrainian: Мараморошський масив, Romanian: Munții Maramureșului), Radna Hills (Romanian: Munții Rodnei), Máramarosi Basin (Depresiunea Maramureșului in Romanian)…

In the south, the vast majority of the population is Romanian, with significant minorities of Hungarians, Rusyns, Ukrainians, Zipt Germans, Jews, and Gypsies. The northern part is predominantly Ukrainian, with significant Romanian, Hungarian, and German minorities. Ukrainians here speak the Hutsul dialect. The linguistic border between the two areas is not sharp and there is some overlap. The borders finalized in 1920 split several settlements in two (e.g. Técső – Kistécső, Romanian and Ukrainian Nagybocskó, Tiszalonka – Lonka).

Here is the article of Horatiu C. Damian:

“The first mention of Máramaros / Maramureș dates back to 1199. It is a document of the Hungarian King Imre (1196-1204). It is a document in which he gives a nobleman in his retinue a beautiful estate as a sign of gratitude. It’s a typical medieval act: the nobleman helps his king in a time of great need, and as a result the king generously awards him.

But what had the nobleman done? He had rescued the king from a great danger that had arisen “cum in silva maramorosensis tempore venationis venatum ivissemus” – while the king was hunting in the woods of Máramaros / Maramures. Having saved the king from this great danger, the nobleman did not leave him in need, but transported him, with great difficulty, until they left the aforementioned forest and arrived in Transylvania, in an inhabited settlement, where the king could receive the necessary care.

A single document from 800 years ago can give us a lot of information. First of all, the king hunted in the forest of Maramureș. That was a huge body of forest, like the famous Silva Blaccorum et Byssenorum or Codrii Vlăsiai. For days and weeks, you could walk through the dark woods and not see the end.

Now we also know that the terrain in Máramaros / Maramureș is rugged. Not easy even today, when most of the primeval forest has disappeared. We can imagine what it was like then when almost everything was covered with thick trunks, creeping vines, bushes, ravines, rocks, and precipices.

The king of Hungary was hunting in the Máramaros / Maramures forest… If there had been any state formation there, either Slavic or Romanian, or customs, or who knows what, the Hungarian king would not have been able to enter as he did, like Vodă through the Loboda. Diplomatic custom from ancient times required that if you wanted to enter someone’s house or state, you had to ask permission.

If Máramaros / Maramureș had a master, the king of Hungary could not enter like that, hey. He should have asked for permission. Or, even better, as it was done in the diplomacy of that time: he would have sent a message to the hypothetical ruler of Máramaros / Maramureș with a letter: “Oh, my honorable cousin (or neighbor, or brother – there were certain codified diplomatic formulas of address between sovereigns), the fame of your hunting grounds has spread throughout the country. My soul longs to test my hunting skills against the beasts your kingdom abounds in. Could you not do me the honor of hunting with me?”

To such an address, to such an elaborate request, what could the ruler of Máramaros / Maramureș (Romanian, or whatever he was, Daco-Romanian, continuing and continuing) say other than “YES, my friend, thought to thought, just now I was thinking of inviting you to hunt the beast that haunts my forests, of Máramaros / Maramureș, which I inherited, as you well know, like all the continuing and continuing Daco-Romans, from Romulus and Remus”.

But it didn’t quite work out that way. Because in Máramaros / Maramureș there was no political formation, no leader. It was just a huge forest. The kingdom of the animals.

The document shows that His Majesty the King of Hungary was accompanied on this expedition by only one man: the nobleman in question. In the mentality of the medieval nobility, hunting was a matter of manliness, a one-on-one, a tussle between nobleman and beast. That’s why, instead of an extended suite (totally inappropriate for a quick expedition through rugged terrain), the king was accompanied by a single nobleman who was his squire, aide-de-camp, second-in-command, bodyguard.

This fact tells us something else: when the king set out on his hunting expedition, he did not expect any trouble from an armed enemy group. Another proof that the Máramaros / Maramureș forest was uninhabited at that time.

The two hunters were after a big game. Not the furry bear or the shaggy and wild boar, I think, but the animals considered noble in the medieval bestiary: the wild boar or the bison. Maybe even the European elk.

What was the great danger that King Imre faced? It was not a clash with enemy fighters. In the mentality of medieval knights, fighting and even dying in a clash with enemy fighters was the pinnacle and raison d’être of chivalry. Had this been the case, the episode would have been mentioned in the deed.

The danger did not come from colliding with one of the “Big Five” – the five large animals that lived in the forests of the region (deer, bison, stag, bear, wild boar). For reasons of identity, the battle with a dangerous beast – a concrete allegory of the iconic battle of St. George with the dragon – would not have gone unmentioned in the document.

Rather, it was an embarrassing situation that was not to be known, and which the nobleman, with the elegance of his class, had sealed under his lips with seven seals. Perhaps the king had fallen from his horse and fallen into a ravine. Perhaps he had lost his horse. It could just as easily have been the problem of the body or a weakness from who knows what medical cause. Under these circumstances, the faithful servant took care of his sovereign and transported him, as only he knew how, to a place where the king could be helped. By the way, the two of them had to leave Máramaros / Maramureș because there was no one there to help them.

Thus, this nobleman earned the generosity of his sovereign.

The first human settlements in Máramaros Maramureș date back to the 13th century: Visk, Hósszúmező (Câmpulung), Huszt, Tecső (Teceu), Sziget (Sighet). There are settlements of Hungarian settlers and western hospices, mainly German. All through the 13th century we know two villages with a Saxon population. But all of them are either on the Tisza river or on the edge of the Máramaros / Maramureș forest.

The inland, hard and unforgiving terrain, required tougher, more energetic people, more accustomed to hardship. The Hungarian kings found them: they were the Vlachs, the ancestors of the Romanians, who began to be colonized in Máramaros / Maramureși in the last quarter of the 13th century. They began to colonize in Maramureș, as a reward for the bravery shown during the second Mongol invasion. They and their companions had that very toughness, that angry temper, and that desperation to find a purpose in a well-governed and prosperous country, as far as possible away from the Balkans from which they had just emigrated. And they were willing to make any sacrifice for it. Including establishing settlements in the middle of an unfriendly forest, far from other human settlements. Exactly this process is so well described by the Moldavian-Russian Chronicle, the highest historiographical achievement of the court of Stephen the Great, written under his supervision and representing the official historical version at the Stephenian court.

It is not easy to take root in the forest or jungle. It took several decades for some places to take root in Máramaros / Maramureș. They are recorded and attested, EXCLUSIVELY from the 14th century. They were inhabited by Romanian nobles, their relatives and vassals, and by the peasant population, also Romanian, serfs and bondsmen, who worked for them.

The main reason for the colonization of Máramaros / Maramureș was to create a defensive zone against a possible new Mongol invasion from the east. This frontier was later to be incorporated into the kingdom. Due to the unfriendly character of the region, the Kingdom of Hungary did not find suitors easily. It took some time before it found those who were ready for such a difficult and dangerous undertaking: the Vlachs/Wallachians. And the incorporation into the Hungarian Kingdom took place in the following way: throughout the 14th century, the nobles of Máramaros / Maramures consolidated their rule there. Towards the end of the century, they, the Hungarian nobles of the Orthodox denomination, formed a county sui generis, with committees (Comes) and vice-comites (vice-comes) elected from among themselves. Then they asked to be incorporated into the kingdom. Which was granted by the Hungarian king of the time.

The history of the Romanians in Máramaros / Maramureș starts from the 14th century.

The Romanian nobles of Máramaros / Maramures were loyal to the Hungarian kings and to the Hungarian state. They fought in Hungary’s wars and defended its territory. The infidel Bogdan de Cuhea was hunted down and expelled from Máramaros / Maramures by the other Romanian nobles of Máramaros / Maramures, after clashes that were no less than those between medieval Scottish clans.

The noble Romanians from Máramaros / Maramure remained faithful in the defense of the Hungarian Kingdom, uninterrupted, from the 14th century until 1918.”

Source: The article of Horațiu C. Damian, (the foreword is from the Hungarian Wikipedia), translated by Google and Deepl Write, by Szántai Gábor

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts:

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital, they are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! and donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfkn