On 27 December 1426, the powerful Hungarian baron of Italian origin, who was known as an exceptional military commander, returned to the Creator. The construction of the fortress chain of the Hungarian border between Szörény and Nándorfehérvár (Belgrade) on the Lower Danube is attributed to him.

Antonio Bonfini, the historian of King Matthias wrote about him: “He [i.e. King Sigismund of Luxemburg / Luxemburgi Zsigmond, reigned 1387-1437 ] forced the Turks to remain in peace in their own country, which he defeated in twenty battles through the Florentine cavalry captain Pipo.” (Antonio Bonfini: Decades of Hungarian History) Originally Filippo was also referred to as Pippo Spano (Comes Pippo) by the Italians but in Bulgarian and Serbian songs and ballads he is called “Magyar Fülöp” (Hungarian Philip).

Long ago, in the 14th century, there was a Florentine merchant called Scolari. He had a son. They lived quite well, but they were not among the rich nobility. In addition to his trade, Scolari had his son trained as a soldier, apparently so that he could protect himself and his goods on his longer journeys. Filippo – as the boy was called – is said to have arrived in Buda at the age of thirteen or fifteen with an Italian agent of a Hungarian lord, where he worked in Luca del Pecchia’s shop. But then he moved on to other things.

Why are we interested in this boy who lived 700 years ago? Did he at least leave something for our time? He wasn’t Hungarian! But he became one, and he had a career in Hungary that was second to none. Our oligarchs of today would be looking at his enrichment with a gaping mouth, and, for that matter, at the professionalism with which he managed his affairs.

Filippo Scolari has an authentic portrayal. Andrea del Castagno’s work, preserved in the San Appolonia Museum in Florence, depicts the young man in armor, sword in hand, with his wavy hair and his lean, wolfish figure. It was not only thanks to his good posture that Filippo caught the eye of one of Archbishop Széchy Demeter of Esztergom. He could read and write and was good at arithmetic, which is how he became first a scribe-deacon to the Archbishop and then a soldier serving in the family. The latter meant indentured military service and came with an oath of allegiance in return for an estate.

Filippo was present at King Zsigmond’s visit to Esztergom and stood behind his master as he listened to his concerns about Turkish attacks on the southern border. The next day, to the great astonishment of the king and his entourage, he put on the table a dazzlingly precise budget for the funds needed to supply the 12,000 cavalry to be sent to the Danube line. A military genius, they said, and the king immediately commissioned him to do the job. Filippo then became a lifelong admirer and supporter of King Zsigmond, and at the same time became deeply committed to the fight against the Turks in the south.

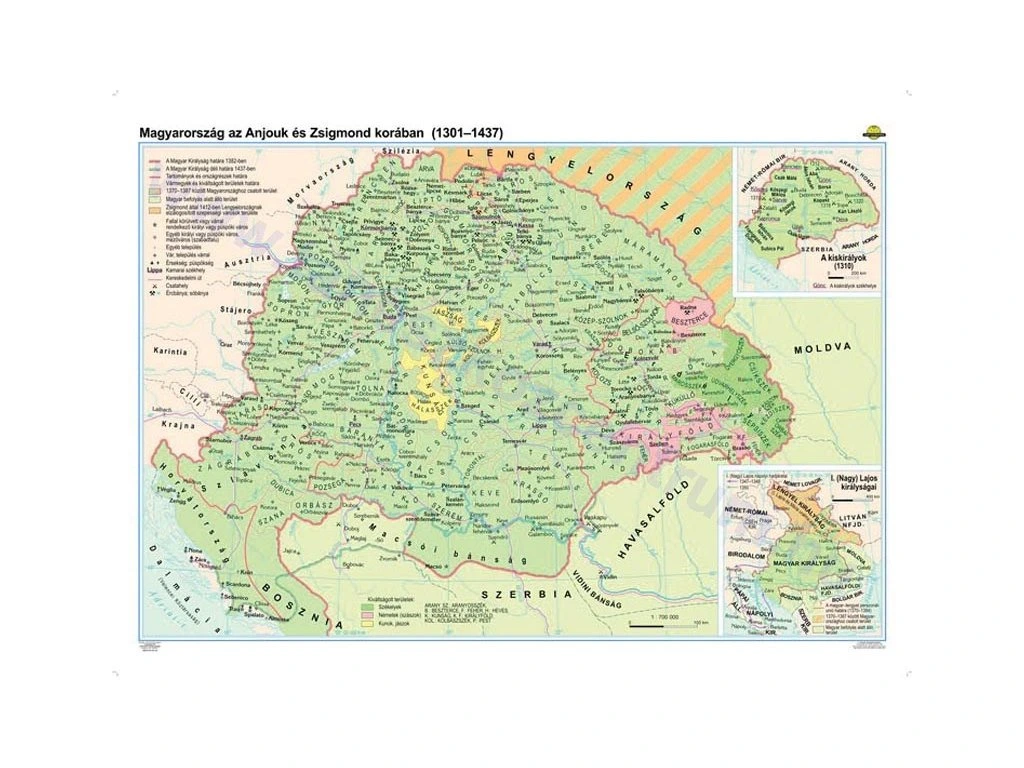

King Zsigmond appointed freshly promoted noblemen to balance the power of the barons. Pipo became one of the king’s allies, on whom the king relied to break the power of the barons who had risen under the Angevins – and who had been strengthened by his lavish donations of land at the beginning of his reign.

Historians record twenty or so major battles against Turkish armies during his lifetime. The southern assignment was accompanied by land grants, but his rise continued even further. In 1394, for example, King Zsigmond, at his suggestion, settled the rebellion of the lords led by the Horváti. His unconditional loyalty to King Zsigmond was confirmed in 1395, during the revolt of the nobles. Filippo played a major role in putting down the rebellion and, according to legend, it was on his advice that Zsigmond executed Kont István and his companions. Through these actions, he grew closer to the king. Also, Scolari stood by the king in the defeated battle of Nicapolis and then, in 1401, during his captivity in Siklós.

At the age of 30, he was already the Lord Comes of the Royal Gold Mines of Körmöcbánya in 1399. This meant that he supervised the mining and made sure that the treasury was not defrauded of either gold or mining fees, he controlled everything with an iron fist so that the king could also entrust him with the supervision of the royal salt mines. Gold and salt were the main resources of the Kingdom of Hungary. Filippo held this position for 26 years. He invested the income from these in increasing his holdings.

He married in his early thirties. He married Ozorai Borbála, the only heir of Ozorai andrás, hence Filippo’s Hungarian name Ozorai Pipó. With the marriage, he obtained control over Tolna County. What did the king give him as a wedding present? More estates. His loyalty to the king continued to grow, especially after 1403 when he defeated the troops of László of Naples who tried to usurp Zsigmond’s throne.

After one of his most important battles against the Turks, he received from Sigismund the title of Comes of Temes, and with it, he won the titles of Comes of the counties of Csanád, Arad, Krassó, and Keve in the south-east of the country, which was all under the jurisdiction of Temes.

From 1406 he was given the title of magnificus, which was granted to barons, from 1407 he was Treasurer-general for a year, and from 1408-1413 he was also the Comes of Fejér County. He was governor of the bishopric of Várad and later of the archbishopric of Kalocsa. In 1408 he was given the title of Baron of Szörény, and as a baron of the country (barones regni) he was one of the founding members of the Order of the Dragon.

He was later made also the Comes of the counties of Csongrád and Zaránd. Thus Pipó became one of the greatest standard-bearers of the country. He successfully governed his province, which covered seven counties, until his death. He also held the royal estates of the counties under his rule, and the king never complained about the income from them.

Meanwhile, the center of the Ozorai Pipo estate became Ozora. He was granted permission to build a castle by the king in 1416, and Pipó and his wife set about erecting a magnificent palace to rival the royal edifices. According to historical sources, he brought an architect from Italy, namely the master architect Manetto Ammantini, whom he knew through his family from Florence and who later became the court architect of Zsigmond. Ozora was just a village but Pipo turned it into a market town with a Franciscan monastery.

When you think about it, the performance of Ozorai Pipo is amazing. His vast estates flourished, his control of the mines was excellent, he fortified Temesvár, Orsova, and Nándorfehérvár (Belgrade), and all the while he excelled as a general. He was also a regular participant in the king’s diplomatic operations and councils. No wonder he became one of the most important authorities in political, legal, and economic life.

During his more than two decades of leadership, Ozorai Pipo gained unparalleled merit in the construction of the fortress system envisioned by King Zsigmond, repelled Ottoman forces raiding the southern regions in several campaigns, and led successful military expeditions to Balkan buffer states such as Serbia and Wallachia. It was during these struggles that the young Hunyadi János began his service in his court, and a few decades later he gained a reputation among the Turks even more formidable than that of his commander. As the young Hunyadi János received the first knightly martial training in Pipo’s court, it is the reason why I think that he must have learned the Italian way of fencing with the longsword.

For a long time, history books taught us that he was a beast. Of course, the Turks and the pro-Turkish peoples of the south thought of him as such. Ozorai Pipo had a good deal of bloodshed among them and often allowed his mercenaries to plunder. These made him a notorious historical figure. His merits were then researched by Italian historians, who provided an objective lens through which to judge him.

For example, an Italian chronicler once wrote: “Pipo was a man of medium height, black-eyed, blond, bright-eyed, and always seemed to be smiling. He was lean in build but in good health. […] He was so cordial and direct that his friends often accused him of not paying enough attention to his dignity. He arranged his house with royal splendor, everything in it glittered with gold and silver. He kept his servants under such control that their virtue could serve as an example to anyone. In his spare time, so far as he had left after the fatigues of war, his rest was chiefly spent in hunting.”

Eventually, Ozorai Pipo’s career as a commander of Zsigmond was even more brilliant than his political career: following his victories in the South, the emperor entrusted him with the command of the Hungarian army during the Venetian War of 1411-12 and the battles against the Bohemian Hussites, but he seldom repeated his successes in the West. The Florentine-born man suffered several defeats in Italy and against Jan Zizka.

In the meantime, Zsigmons had also “tried out” his old confidant as a diplomat, so Ozorai Pipo took part in the delegation’s trip to Pisa to negotiate with the antipope John XXIII, and during the Council of Constance (1414-18), which ended the schism in the Western Church, he was assigned to guard the above-mentioned cleric, who had been forced to resign.

In the last years of his life, Ozorai Pipo returned to the leadership of Temes County: in 1423 and 1425 he fought in Wallachia to secure the rule of the Voivode Dan II, who sought the patronage of Sigismund. Pipo was suffering from gout towards the end of his life and is said to have led his last Turkish campaign from a litter. This was the now-forgotten triumph of Galambóc (Golubac). On 4 November 1426, he still attended the council meeting at Lippa to discuss a new campaign in Wallachia. It was the place where he died.

The merits of Ozorai Pipo and the role he played in the political life of Sigismund’s time are perhaps best illustrated by the fact that he was laid to rest in Fehérvár, and the emperor himself paid his respects at his funeral. They buried him in the chapel he founded in the Coronation Basilica in Székesfehérvár. On his tombstone, in the 16th century, one could still read the inscription: ‘The tomb of the valiant and great Sir Scolari Fülöp of Florence, Count of Temesvár and Ozora. He died on 27 December 1426.” His date of birth is unknown, but scholars estimate that Pipó lived between 56 and 58 years. But what is certain is that for over forty of those years, his motto was “With Zsigmond and for Zsigmond!”

Sources: Naptármesék, and Tarján M. Tamás

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts:

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital, they are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! and donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfkn