Rákóczi Ferenc II, Prince of Transylvania and Hungary, the second child of Rákóczi Ferenc I and Zrínyi Ilona, was born on 27 March 1676 in Borsi Castle. He is a descendant of important Hungarian and Croatian aristocratic and even princely families.

His father, Rákóczi Ferenc I, was given the title of Prince of Transylvania as a child, although he was never allowed to rule. However, his ancestors, great-grandfather and grandfather, Rákóczi Zsigmond and Rákóczi György I and II, sat on the throne of Transylvania. On his mother’s side, he was a descendant of the famous Croatian family, the Zrínyis (Zrinski), his great-grandfather Zrínyi Miklós (Nikola Subic Zrinski) died a heroic death defending Szigetvár, and his grandfather Péter (Petar) was one of the leaders of the Wesselényi conspiracy and ended up on the scaffold. Let us not forget that Petar’s elder brother was the famous general and poet Zrínyi Miklós (Nikola Zrinski), who died in 1664.

Rákóczi Ferenc’s father was also involved in the movement but managed to save his life at great financial cost. Through his paternal grandmother, Báthory Zsófia, he was related to the Báthory family, also princes of Transylvania. The titles and expectations of princes, the symbols of the resistance of the Hungarian estates against the Habsburgs, and the tradition of anti-Turkish heroism were all united in Rákóczi Ferenc II.

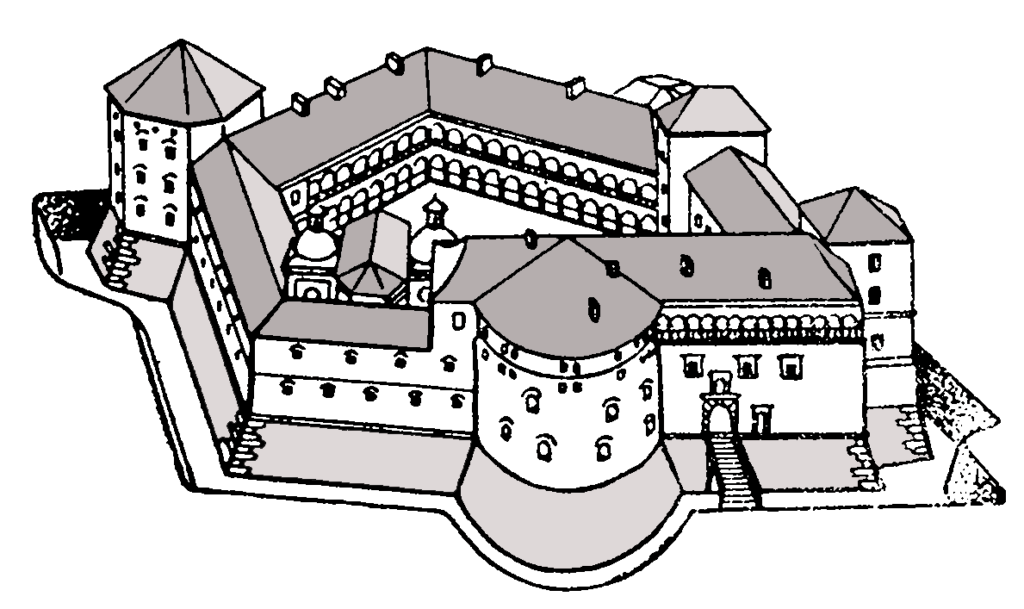

According to Thaly Kálmán, Márki Sándor, Várkonyi Ágnes, and Köpeczi Béla, the reason for his birth in Borsi was that his mother, Zrínyi Ilona, had fled from Sárospatak to Munkács to escape the rebels (Kuruc troops) surrounding the Rákóczi estates. Still, she had to stop at the small castle of Borsi. It was here that the future leader of the War of Independence, Rakóczi Ferenc II, was born.

His father died shortly after the birth of Ferenc, so that Rákóczi would have been under the guardianship of King Leopold I, but Zrínyi Ilona managed to get him to be raised among her children.

Three months later (on July 8th) in Zboró died Rákóczi Ferenc I, leaving behind Zrínyi Ilona to raise little Ferkó and his sister Julianna. He was educated like a prince, consciously prepared for the government. The mother soon became the wife of Count Thököly Imre, so Rákóczi spent most of his childhood among the fugitives in the family’s castle in Munkács. He took part in the campaign of his stepfather, Thököly Imre.

Zrínyi Ilona not only defended the walls of Munkács against Caraffa for two years but also her children. After the capitulation, the father’s will was carried out, and Julianna and Ferenc became the wards of Leopold I.

The son was sent to Prague by Archbishop Kollonich Lipót to study. He graduated from the university and grew into a broad-minded man, well-versed in the sciences, government, and economics. However, the ‘rebellious Hungarian blood’ was not squeezed out of him, for he married, in 1694, in defiance of the King’s plan, to Princess Sarolta Amália of Hesse. His wealth, fame, international reputation, and knowledge eventually made him the leader of an anti-Habsburg uprising.

Rákóczi was sent to his family estates, to Sáros County, where the Kuruc rebels in hiding immediately tried to put him at the head of their movement. He refused in 1699, but by 1700, he was writing letters to King Louis XIV of France, asking for help with a planned uprising. However, his messages were passed on to the court by his confidant, Longueval, who betrayed him. Thus, Rákóczi was arrested in his castle of Nagysáros, taken to Vienna, and awaited death.

With the help of his wife and brother-in-law, however, he escaped and fled to Poland, where he rejoined Bercsényi Miklós in contacting the French court and awaited the right time for an uprising. Let us note that Rákóczi was also the richest landowner in the country and was able to rally a large segment of society behind him.

This came in 1703, when the Habsburgs, finding themselves in a difficult position, withdrew most of their troops from Hungary during the War of the Spanish Succession (1700-14).

In the Manifest of Brezán, in Poland, Rákóczi and Bercsényi issued a document to call the inhabitants of Hungary, both nobles and serfs, to arms on 12 May 1703. Rákóczi accepted the request of Esze Tamás and his Talpas (foot soldier) troops and took the lead in the Kuruc movement around Munkács, which was initially joined mainly by the Hajdú soldiers, serfs, and the former Thököly refugees who had remained in the mountains.

The text of the Manifest of Brezán:

“We, Prince Rákóczi Ferenc of Felsővadász and Count Bercsényi Miklós of Székes. To all true Hungarians, patriotic and longing for the old glorious freedom of our dear country, clerical and lay, noble and common, armed and at home, we wish all the best from God.

There can be no Hungarian who has not sufficiently felt and understood the cruelty of a foreign nation, the intolerable taxation, the interference with our free laws, the contempt for our nation and our freedom, and the mockery that we had already been conquered.

So much so that no one could have condemned anything but the grave danger to our country, to our ancient freedom, if the merciful God of all empires had not surrounded the German nation, which had hitherto oppressed our country, on all sides with miraculous and unexpected wars, and had not thereby shown our Hungarian nation, which bitterly longed for its old freedom, the way out, Thus, the time and the means of liberation from the great yoke of evil have been declared to be so opportune that our country can never hope for a better, more favorable or more certain opportunity.

So that we may dedicate all the days of our lives and our fate, which we have been driven into bitter exile against the law and our noble liberty, to the ancient liberty of our sweet country, to the former good name and name of our glorious nation, and the good and benefit of the inhabitants of our country, now in a state of depression; moreover, for the more urgent strengthening of our efforts, we have not failed to rely on the help and understanding of kings and princes who have been saddened by the impossible distress of the Hungarian land and have been useful to our country.

Now is the time to free our country once again from such an unjust and implacable yoke: we exhort and urge to patriotism all true Hungarians of all classes, noble and common, men-at-arms and men-at-home, in a word, all true Hungarians of all ranks, who love their country and owe their duty to their country, that God has already stirred up and united the hearts of some for the sake of the fatherland:

Let every man, for his dear country and nation, for his liberty, take up arms against the empire that imposes, harasses, oppresses, taxes, violates our noble liberty, despises our true ancient laws and goods, seizes and consumes our goods, tramples on our honor, takes our salt and bread, and rules and cruelly governs our lives, against God and our law.

That all the men-at-arms, true patriots, even before we emerge, be in agreement with the officers and officers’ bands to whom we have entrusted the initiation of this cause, and that, even until we do come out, the subjects of those officers and officers to be made by them shall be obedient, and others shall live in a common good sense; Being assured that we shall go forth without delay with a sufficient army of helpers, and for our dear country, our nation, our ancient liberty, with the help of Almighty God and the strength of His mighty arm of war, with perfect heart and soul, consecrate our lives and shed our blood for the sake of our nation and our country alone, without any desire for anything private, we will be ready.

We also believe in the merciful God who hears the cries of the widow and the orphan, the bitter and the distressed, and in the ancient and glorious warlike courage of our nation, which is still alive today, and in the zeal of our people for their homeland, and in the help of the great kings and princes who have joined us in this, that in this opportune time, granted by God alone, we may achieve and restore the ancient liberty of our nation, by the labor of all our hands, and end our days in a state of glorious freedom, blessed by God, both for ourselves and for our posterity, with the perpetual survival of our country.

Nevertheless, we forbid it in advance with a great prohibition, so that the blessing of God may remain upon us, the country may be trusted without any religious abhorrence, and the whole misery of poverty may be redeemed, not changed: No man, either singly, or with a group, or with an army, of any religion, of any church, cemetery, cloister, clergy, persons of noble birth, noble houses, castles, travelers, merchants, shall disturb, burn, or plunder any village, town, or mill; but in all things, with quiet and godly understanding, seek the enemy according to the manner given by the leaders, for their own good and the good of their country.”

The War of Independence

Rákóczi sent his flag, with the following text on it: „Cum Deo pro Patria et Libertate” – “With God, for the Nation and Liberty”. After the flag was lifted up at Tarpa, the eight-year-long struggle for freedom broke out. However, the freedom struggle’s room for maneuver was limited by the lack of foreign aid and the country’s isolation.

Rákóczi’s unsuccessful struggle cannot be separated from the Habsburgs’ war in the West: the Kuruc rebels had their greatest successes at a time when the imperial court was in a crisis, and it is no coincidence that they reached the Danube in 1703, and even captured most of the Danube region, and soon raided the area around Vienna.

In 1704, however, the Anglo-Dutch-Austrian troops won a great victory over the French army at Höchstädt, and this had an impact on the Hungarian Kuruc uprising: slowly but surely, their decline began, which was masked for a long time by local successes, the election of Rákóczi as Prince (1705) and the Habsburgs’ dethronement at Ónod (1707).

However, the favorable negotiating position of the Kuruc army in 1703 was lost, and after the defeat at Trencsén (Trenčín) in 1708, the last chance of victory was gone.

Rákóczi tried in vain to gain diplomatic support from Louis XIV (r. 1643-1715), Prussia and Tsar Peter the Great (r. 1682-1721). The country became impoverished under the burden of war, a plague broke out in 1710, and fighting became less frequent.

The following year, Rákóczi traveled to Poland to finally obtain support from the Tsar, but Károlyi Sándor, who was in charge of negotiations, reached a peace agreement with the imperial commander Pálffy, and the Kuruc laid down their arms at Szatmár.

Read more about Pálffy’s life here:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/famous-people/palatine-palffy-janos-1664-1751/

Rákóczi later did not admit this, calling Károlyi a traitor, but from a realpolitik point of view, the treaty imposed very mild conditions, granting impunity to the prince himself. At the time, he was in negotiations with the Russian Tsar Peter I of Russia – and the peace of Szatmár, concluded in his absence, was favourable to Rákóczi under the circumstances.

He was granted a pardon and could keep his property if he took the oath of allegiance in three weeks.

If he had not wanted to stay in the country, he could have left for Poland. He did not accept the terms of the peace; however, he did not trust the sincerity of the court and considered Pálffy’s mandate invalid because of the death of King Joseph I of Hungary.

Thus, Rákóczi refused to accept this, stayed in Poland, and went into ‘hiding’, trying to get help to restart the uprising on French and Turkish soil. France, however, was not interested after the Peace of Rastatt (1714) and the death of Louis XIV (1715), and the Turks refused to enter into conflict with the Habsburgs after the Peace of Posseravati (1718).

In exile

And in Poland, a crown awaited him. The Polish Estates offered him the Polish crown twice. His election was supported by the Russian Tsar, but he did not accept. He had no place to stay…

On 16 November 1712, he sailed from Poland to England but was not welcome there. He was not received by Queen Anne of Great Britain because of the objections of the court at Vienna. His next stop was France. Although not officially recognised by the French court, the prince was in great favour with them, but after the death of Louis XIV on 1 September 1715, he was no longer comfortable here.

In 1717, he was approached by Sultan Ahmed III to organise a new uprising of Kuruc soldiers and national resistance fighters, for which he promised military assistance and 2.5 million gold pieces. Not coincidentally, the Turks were engaged in one of their ‘usual skirmishes’ with the Austrians, and any help would have been welcome. Although the conspiracy was carried out with great force, it was not successful. There were some Kuruc troops among the Turkish armies invading Hungary, but they were unable to persuade the people to revolt.

The campaign of Esterházy Antal in Transylvania also failed because the Kuruc soldiers who arrived with the Crimean Tatars were received with hostility by the population. The invading Tatars were more barbaric destroyers than allies. It was the last Tatar incursion against Hungary.

It was not a very good idea to cherry-pick from the same bowl with the Turkish Sultan… However, it is certainly to the Sultan’s credit that in the peace treaty of Pozsarevac concluded on 21 July 1718, the Porte flatly refused to extradite the fugitives. Two years later, the imperial envoy still demanded their extradition, but the Sultan, invoking the Sultan’s honour and the Quran, declared that he would not dare to do such a dishonourable thing.

All he did was to relocate the fugitives to Rodosto, a short distance from the capital. The prince made his new home in this town by the Sea of Marmara with a handful of loyal followers. Rákóczi’s voluntary exile and his refusal to negotiate with the Viennese court symbolized the main goal of his life, the independence of the nation.

Before his death, he made arrangements for the family and comrades he left behind. He commemorated each of them with a donation in his will of 27 October 1732. In a special letter to the Grand Vizier and the French ambassador to Constantinople, he asked them not to forget the orphaned fugitives after his death. He died in Rodosto in 1735.

His loyal chamberlain, Mikes Kelemen, took his body to Constantinople on 6 July 1735, after receiving the permission of the Porte, and buried it in the Church of St. Benoît, or St. Benedict, in Galata, then in the hands of the Jesuits, next to his mother, Zrínyi Ilona, following his will.

His person and his fight for freedom are remembered in Hungarian legend, and his figure has become a symbol of Hungarian freedom and endurance to the end, especially because he was willing to go into exile for his cause.

Decades after his death, his “most devoted nation,” the Ruthenians around Munkács in the Subcarpathian region, still put an extra plate and chair on the table every day in case Rákóczi should return.

Source: Rubicon (Tarján Tamás), Magyarforum, and Szibler Gábor

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

If you like my writings, please feel free to support me with a coffee here:

or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: http://Become a Patron!